Forevermark pear-shape diamond at a grading facility in Antwerp, Belgium. Photo by Nicholas Andrews

Rocks My World

What Is A Diamond?

The lab grown gems hitting the market give the question a sense of urgency

What is a diamond? I have been giving the question a lot of thought lately with the abundance of lab grown diamonds hitting the market. A scientist will tell you a diamond is pure carbon. I believe it is much more.

There are at least 10 companies around the globe elbowing into the fine jewelry world with the pure carbon stones they are generating in epic ovens. All kinds of deceptive names have been attached to these creations. One of the most misleading I have been seeing lately in the press is “diamonds sourced from above the ground.” No other qualifier is attached to the phrase. While the rocks may have the appearance of natural mined diamonds, gemologists can tell if they are from the earth or not with the right equipment. There is also something soulful missing from the manmade shiny baked bits of carbon—historical significance, symbolism and, yes, love.

The origin story of diamonds is part of their beauty. Formed in the earth billions of years ago, before the age of the dinosaurs, diamonds were brought closer to the surface by volcanic eruptions. No one knows exactly when diamonds were first used for adornment, but it was in ancient times. Pliny the Elder, a Roman essayist, wrote in his Natural History published in the first century, “The diamond, known for a long time only to kings and then to very few of them, has greater value than any other human possession and not merely than any other gemstone.”

The public’s fascination with royal diamond jewelry is as strong today as ever. There is a sense of awe at the value, the rarity and the physical manifestation of history in something so beautiful. Two million people a year visit the Tower of London to see some of the largest diamonds in the world among the British Crown Jewels. The Hope Diamond, which is believed to have once been part of Louis XIV’s collection, has long been the most popular display at the Smithsonian Museum.

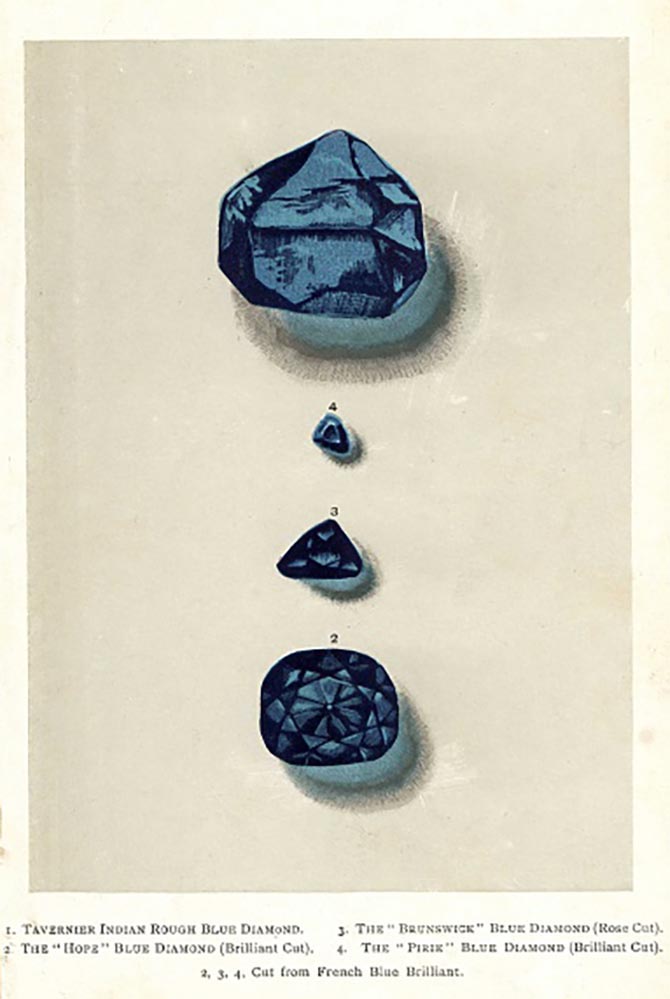

Chromolithograph by an unknown artist from Edwin Streeter’s 1892 publication ‘Precious Stones and Gems’ depicting blue diamonds: the Tavernier Indian rough blue, the Brunswick blue, the Hope diamond and the Pirie blue. Photo Florilegius/SSPL/Getty Images

As symbols of love, cynics like to say, a marketing campaign made diamonds popular for engagement rings. “A Diamond Is Forever,” one of the great ad slogans of all time, certainly helped popularize diamond engagement rings when it originally started running after World War II. Yet, the history of diamond engagement rings goes back much further. The first date to the eighteenth century, some say earlier.

In 1886, Charles Lewis Tiffany brought the modern diamond engagement ring into vogue with the Tiffany Setting. He knew Americans wanted a bit of the fairy tale romance of royalty. When Eleanor Roosevelt received her Tiffany diamond ring from Franklin Roosevelt in the fall of 1903, she wrote him a letter saying, “You could not have found a ring I would have liked better.” I really can’t imagine the same sentiment would be true for something created in an oven in two weeks.

Diamonds are a beloved metaphor for poets and musicians. Tom Waits’ lyric, “Always keep a diamond in your mind,” has no magic if you think of the stones being cooked. Change Rihanna’s signature line to “Shine bright like a lab grown diamond” and the song is a disaster. The opening of the late great Tom Petty’s “Walls,” “Some days are diamonds and some days are rocks,” loses all meaning if diamonds are not diamonds as we know them.

The lab grown folks are playing God with their mineral creations and fouling up so much of the miracle of nature not to mention adding a layer of confusion in the marketplace. They are selling their product at prices that are only slightly less than diamonds from the earth and have a tone that sounds as though they believe they are saving the environment. The very definition of sustainability for a business means it takes into consideration environmental, social and ethical issues. The lab grown company Diamond Foundry says its 100% carbon neutral, but that’s not the same thing.

Few journalists, besides Rob Bates at JCK, have bothered to get the counter points on the issues of the environment from jewelers. Many have sustainability programs in place. Tiffany, the inventor of the modern engagement, has an expansive sustainability program outlined on its website. Forevermark, as part of the De Beers Group, also participates in an impressive sustainability program.

Rough diamonds arranged on a light box at the De Beers office in London. Photo Nicholas Andrews

For every hectare (or 10,000 meters) of land the De Beers Group mines, it donates 6 acres to a series of conservation and research sites it supports called The Diamond Route. Preservation of land, wild habitats and ecosystems are priorities. They are also working to save the white rhino from extinction and protect cheetahs. De Beers has training programs to further the advancement of women in an array of jobs within the diamond industry including managers, engineers and geologists. They have enterprise development programs to assist local businesses, especially those owned by women.

I was reading about lab grown diamonds on Wired—yes, Wired—the tech folks are fascinated by the luxury turn of some of their own. Anyway, another story on the site caught my attention. It was on the morality of artificial intelligence. It got me to thinking. One of the many questions about lab grown gems is a moral issue. Just because you can make something that looks like a diamond should you?

In Botswana, De Beers works hand in hand with the government running the diamond mining business that accounts for 25% of the gross national product of the nation. The industry has helped make the economy one of the fastest growing in the world, creating jobs. If the production was replaced by material grown in a lab, it would destroy communities in Botswana.

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER