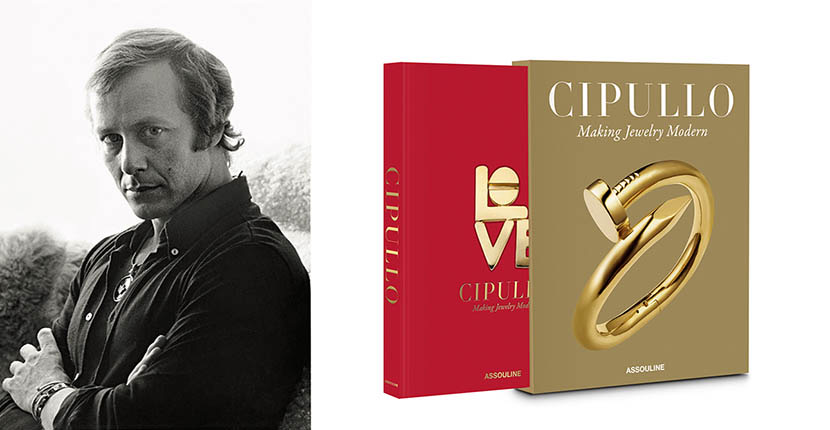

Aldo Cipullo wearing a Scorpio pendant and a Nail bracelet, c. 1977 and his new biography Cipullo: Making Jewelry Modern. Photo Oscar Buitrago, All Rights Reserved, Courtesy Renato Cipullo and Assouline

Books & Exhibitions

The Man Who Invented Modern Love in Jewelry

A lavish biography of Aldo Cipullo has finally been published

I fell under the spell of Aldo Cipullo’s charms in 2012. It was the year Cartier relaunched Aldo’s Juste un Clou bracelet with an exhibition titled “Cartier and Aldo Cipullo: New York City in the 70s.”

I wrote the storyline for the exhibit, that was staged at the Cartier Mansion. During the course of my research, the brilliant archivists at the firm presented me with what felt like a foot-high stack of interviews Aldo had given to the press over the years he worked at Cartier. Reading these stories is how I became enchanted with the designer.

Aldo had a magical way with words and knew how to give a good interview about his Cartier designs and the changing mode of jewelry in the 1970s. All of the coverage provided a lot of the designer’s thoughts and ideas first hand. Just a few of my favorite shorter quotes from Aldo are following:

I believe in radical change in jewelry. It should be more fun! If you have a Louis XVI desk you can have a Le Corbusier chair next to it. It’s the same with jewelry.

I select a stone as I would a room décor, after all, color is a state of mind.

A piece of jewelry should never come before the person.

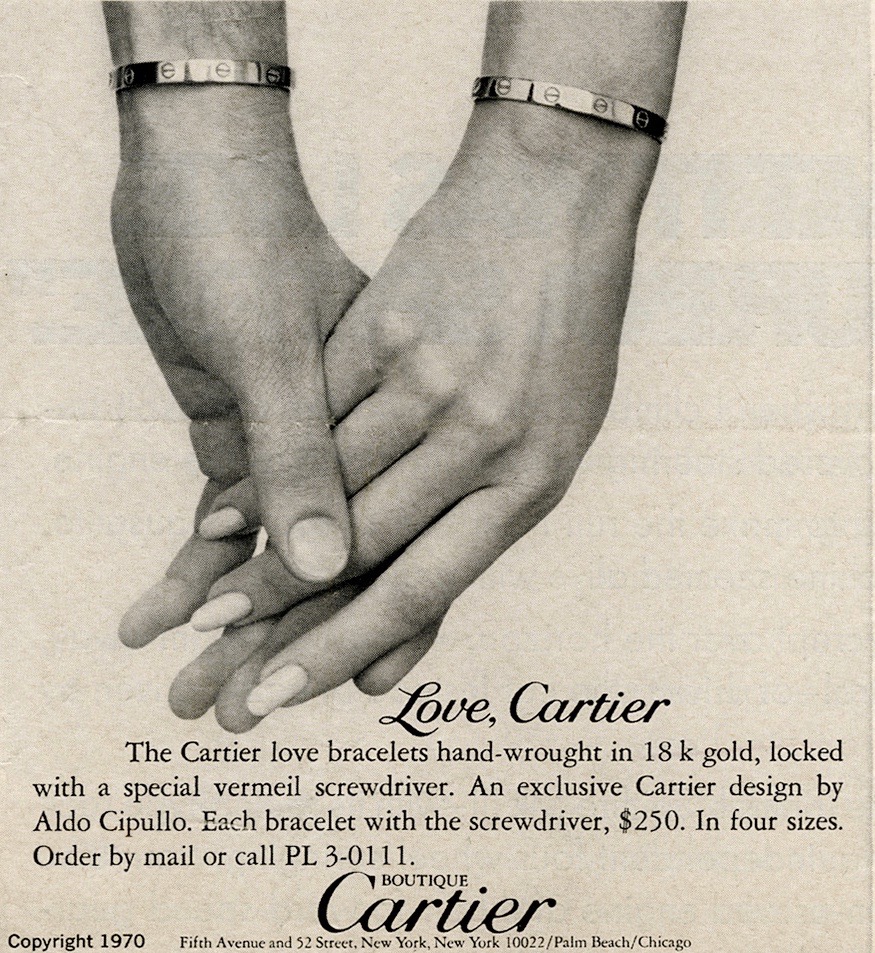

A 1970 ad for the Love bracelet shows it being worn by a man and a woman. Photo © Cartier

Now more of Aldo’s life story has been told from the perspective of Aldo Cipullo’s brother Renato Cipullo and jewelry writer Vivienne Becker in the Assouline publication Cipullo: Making Jewelry Modern. The oversized book has lots of great and personal photographs of Aldo, a blonde, blue-eyed Italian with movie-star good looks. There are also a number of his drawings and jewels from his years at designing for Tiffany, Cartier and under his own name.

The story covers the Italian designer’s youth in Rome where he worked for his father Giuseppe’s eponymous costume jewelry company. Aldo moved to New York in 1959 where he continued his education at the School for the Visual Arts. Then he landed a job as a bench jeweler at David Webb. The esteemed American designer, who also knew how to work on the bench, apparently told Aldo to call himself a designer as opposed to a bench jeweler.

Button ear clips combining yellow gold and chrysoprase designed by Aldo Cipullo for Cartier, 1972-74. Photo Marian Gérard, Cartier Collection © Cartier

Not much more seems to be known about Aldo’s three years at David Webb, but the designer kept an archive of his work at Tiffany where he was employed for three years. Renato and Vivienne draw on this ephemera and memories to tell the story of Aldo’s achievements with one of the esteemed Tiffany teams at the time that was led by Gene Moore and included the spectacular design talent, Donald Claflin. For his part Aldo explained, “We all design together.”

The pictures in the book show how Aldo was very much working in the Tiffany decorative mode of the late 1960s. There were lots of jewels featuring colorful flora and fauna. One of my favorite Cipullo designs of the era was his ornate Swan ear cuff that was featured in the November 1, 1967 issue of Vogue on a model shot by Bert Stern. It seems wildly ahead of its time.

Bracelet in 18-karat yellow gold set with carnelian, designed by Aldo Cipullo for Cartier, 1972. Courtesy Sotheby’s, Inc. © September 23, 2014

According to Renato Cipullo, Aldo offered the Love bracelet design to Tiffany near the end of his contract in 1969.

If this is accurate, it seems actually quite natural that Tiffany passed on the jewel. It wasn’t anything like the work Aldo had been making for the firm. Apparently, Aldo then offered it to the president of Cartier New York, Michael Thomas. A visionary marketer, Thomas totally understood the design and clearly had lots of ideas about how to sell it. (Find out more about the history of the Love bracelet here.)

Love brooch in yellow gold with a screwhead for the letter O, designed by Aldo Cipullo for Cartier, 1973. Photo Steven DeVilbiss © Assouline

Cipullo began contributing work to Cartier in 1969 after they acquired the Love bracelet design. He joined a super talented team that included Alfred Durante who was responsible for some of the pieces commissioned by Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton during the period.

At Cartier, Cipullo became a media star because the firm connected him with the press for all those fabulous interviews about his Love bracelet and the Juste un Clou as well as several other collections he designed in a range of themes that reflected life in New York City during the early 1970s including the Women’s Movement, Pop Art, Minimalism, signs of the zodiac, backgammon and good luck charms. Each is detailed in the book.

The visuals show how some collections were delightful and inextricably linked to the era. Others, of course, have long since withstood the test of time and become among Cartier’s iconic modern jewels.

Cartier advertisement for the Backgammon pendant of yellow gold and enamel, designed by Aldo Cipullo for Cartier, 1973. Photo © Cartier

Cipullo’s glory days at Cartier came to an end in 1974 when the administration of the firm changed. At this point, Cipullo began to focused on his own label and expand his offerings to include home accessories, furniture, leather goods and costume jewelry.

Cipullo’s fine jewelry designs continued in several of the modes he had created over the years at various firms. There was some modern gold jewelry and decorative flora and fauna designs. Cipullo remained popular with the press and won the prestigious American Fashion Critics Coty Award for his men’s jewelry in 1974.

Tragically, Aldo’s story came to a premature end in 1984 when he died at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City. The cause of death for the 48-year-old was listed in The New York Times obituary as a double heart attack. The cardiac arrest may have been caused by a larger health issue.

Related Stories:

Cartier’s Love Bracelet Was Conceived In NYC

An Iconic Watch Makes A Big Comeback

Elsa Peretti’s Iconic Bone Cuffs Reimagined

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER