Elsa Peretti looking in a mirror in front of her inspiration board during the 1970s. Photo by Hilda Moray via Instagram @elsaperettiofficial

Jewelry History

Memories of Elsa Peretti

The influential jewelry designer transformed Tiffany

March 21, 2021—“I design for the working girl,” explained Elsa Peretti in a 1974 interview with People magazine shortly after her launch party at Tiffany that attracted over 2,000 fans. “What I want is not to become a status symbol but to give beauty at a price.”

The 80-year-old designer who died on Thursday night in her sleep at home in Spain put Tiffany in touch with what was happening on the street in the seventies by making affordable designer silver jewelry and stylish diamond necklaces with a starting price point of $89.

Her work was just right for the economic crunch of the era. The other part of the appeal was Elsa’s jewels matched the new laidback high fashions. The line she made with the working girl in mind was also a big hit with the elite Ultrasuaves, a nickname for trendsetting women like actress Liza Minnelli, art collector Ethel Scull, and Vogue editor-in-chief Grace Mirabella, who wore Halston Ultrasuede.

Elsa Peretti taking a call at her jewelry counter at Tiffany during the 1970s. Photo Getty

How an Italian designer changed America’s most celebrated jewelry store overnight is a story with twists and turns. The daughter of Maria Luigia and Ferdinando Peretti, founder of the API oil company, Elsa Peretti was born in 1940 in Florence and brought up in an atmosphere of privilege. At 21 she left home to teach languages and skiing at her old Swiss boarding school. Next, she got an interior design degree in Rome and worked for an architect in Milan.

In 1966, Peretti relocated to Barcelona where she became a model and as she put it, “began to create the basis for a different approach to life.” Two years later she moved to New York City.

“When I arrived in New York, there was a garbage strike and I thought I was in hell, then I met Giorgio di Sant’Angelo,” Elsa told Penny Proddow and I when we interviewed her for our book Bejeweled: Great Designers, Celebrity Style.

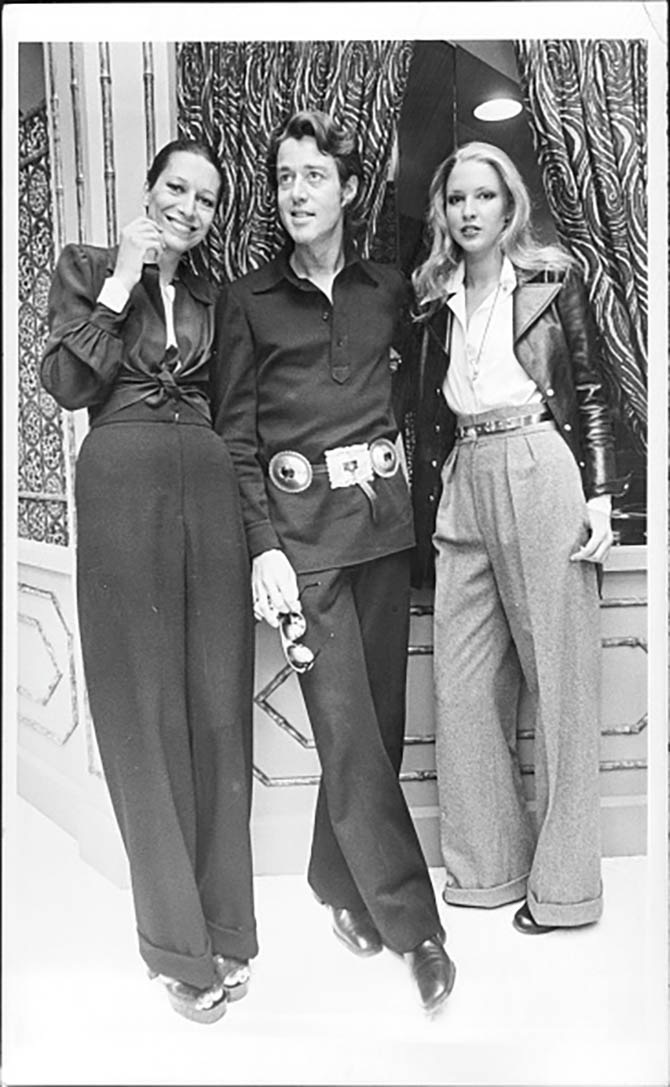

Elsa Peretti with Halston and another model at a 1971 event in Bloomingdale’s. Photo Getty

A top Italian fashion designer working in New York, di Sant’Angelo and Elsa became fast friends and she found herself at the very center of the happening fashion scene. Working as a model, she was a favorite of photographer Helmut Newton and a muse and close friend of Halston.

All the while, Elsa was still searching for a way to express her own creativity. When she discovered what she wanted to do, she told di Sant’Angelo, “It’s going to be jewelry.”

Though the decision seemed somewhat spontaneous, her first jewels—an organic bottle pendant and a heart-shaped belt—were an instant success when di Sant’Angelo and Halston both showed them on their runways. “A lot of people liked the bottle,” remembered Elsa. “And I continued to model to pay for the production.”

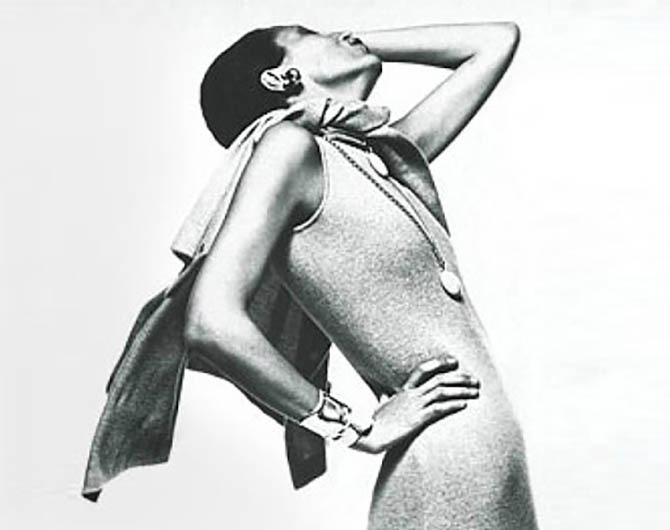

A 1971 image of Elsa Peretti wearing Halston and early renditions of her Bone cuffs and Bottle pendants. Photo by Chris von Wangenheim via Pinterest

In 1972 Peretti’s collection was picked up by Bloomingdale’s. The department store organized Cul de Sac, a special boutique to showcase Peretti’s work and that of other up-and-coming young designers, including David Yurman and M + J Savitt.

In 1974, Peretti made the move to Tiffany. “It all happened when George O’Brien, the art director at Tiffany, spoke to [fashion editor] Carrie Donovan, who spoke to Halston, who spoke to me, and set up the meeting,” remembered Peretti. She showed the executives her Bottle pendant and then immediately signed a contract to work for the jeweler.

Silver jewelry with shapely curves have defined a major portion of Elsa’s work at Tiffany. “Touch is important: I get lots of my inspiration from tactile things, maybe because I don’t see very well,” Elsa told the New York Post about her style in June of 1971.

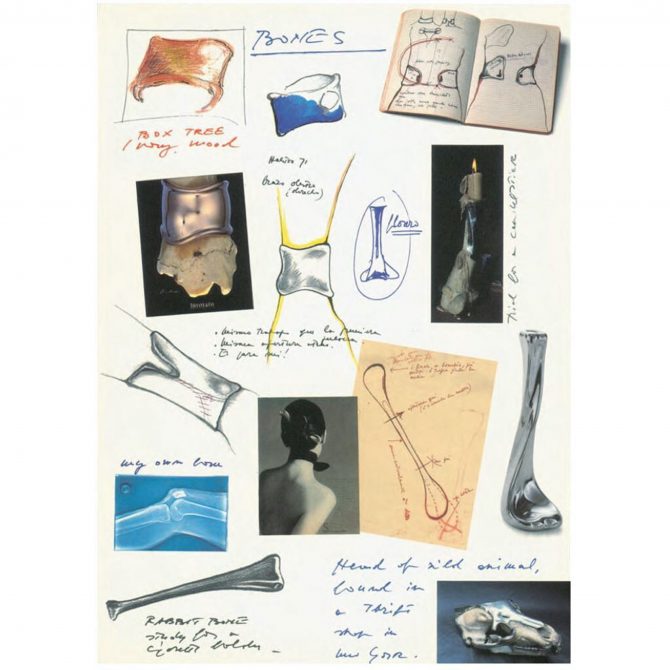

Page from, Fifteen of My Fifty With Tiffany, the Elsa Peretti-FIT retrospective catalogue showing her drawings of the Bone cuff, Xray of her leg and Hiro advertisement of the jewel among other things. Photo via

Another consistent quality in all of Elsa’s work is that personal, often quirky events, inspired every creation. In Fifteen of My Fifty With Tiffany, the retrospective catalogue for Elsa’s 1990 exhibit at FIT in New York, she explained about her iconic Bone Cuff:

My love for bones has nothing macabre about it. As a child, I kept on visiting the cemetery of a seventeenth-century Capuchin church with my nanny. All the rooms were decorated with human bones. My mother had to send me back, time and again, with a stolen bone in my little purse. Things that are forbidden remain with you forever.

Elsa was also clearly interested in the shape and structure of bones much in the same way as Georgia O’Keefe. A page from her catalogue above she shows an X-ray of her own bones.

Vintage gold Elsa Peretti for Tiffany snake necklace. Image via Instagram particulieres.nyc

Elsa’s snake necklace wasn’t inspired by the long history of snakes in jewelry. The idea sprouted from a rattlesnake tail a Texan she met in Lausanne, Switzerland gave her as a good luck charm.

“I thought Americans have to be brave, having these kinds of snakes in their backyards,” explained Elsa in Fifteen of My Fifty. “I kept the object with me for many years.”

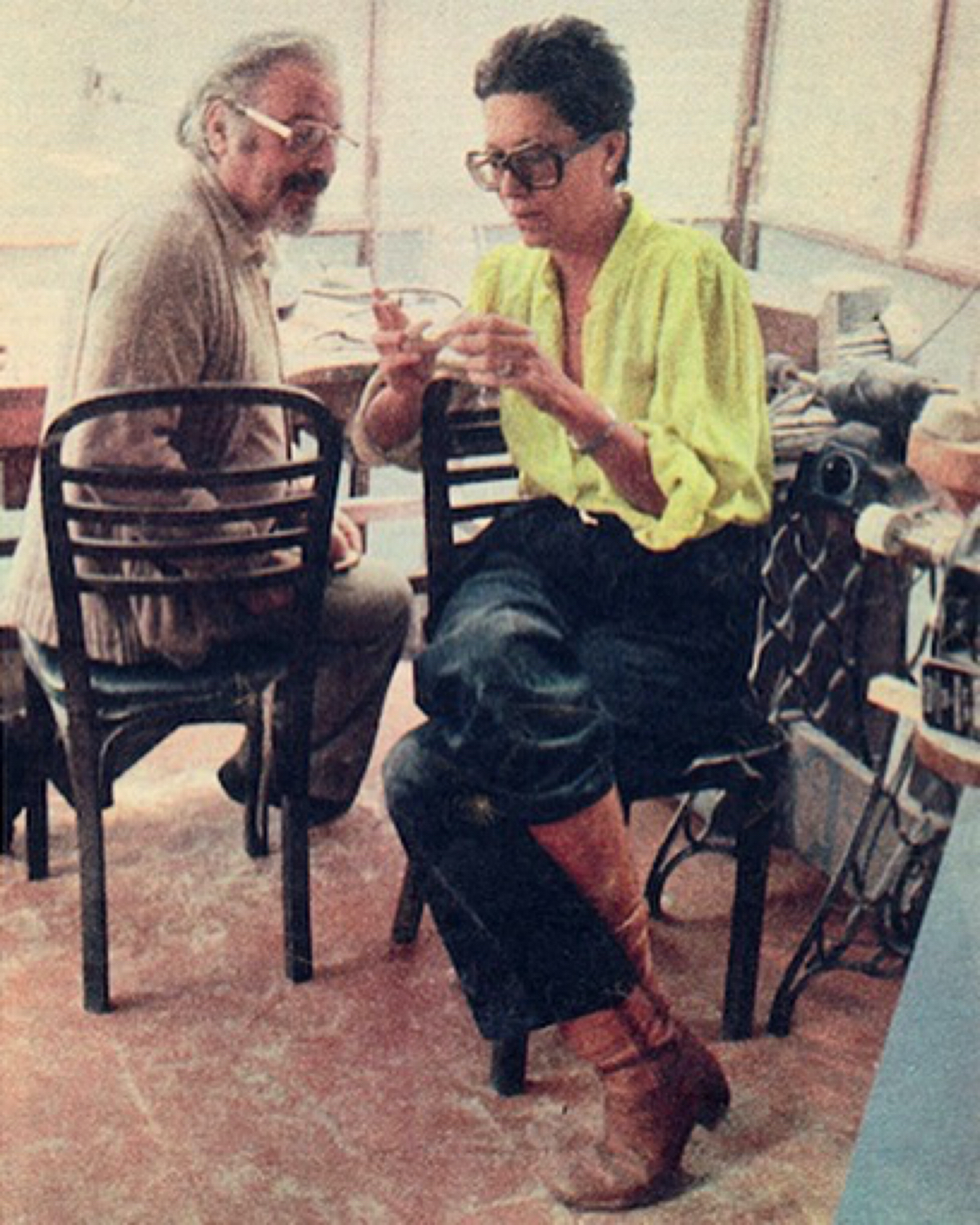

Elsa Peretti working on a jewel with señor Costas in 1978. Photo via Instagram @elsaperettiofficial

A third important factor that plays into Elsa’s history is that she consistently gave credit by name to the craftsmen that helped her conceive her designs. In 2009 for Elsa’s 35th anniversary she produced a Tiffany ad with a Hiro photo of her sketchbook, glasses and an apple artfully arranged on the ground in the sunlight with the phrase, “Thanks to everybody who will continue to work with the spirit of a craftsman, and without whom we will never realize our fantasy.” Elsa once said of herself, “I am not an artist, I’m a craftswoman.”

When I asked her about the genesis of the bump for the wrist bone in her Bone cuff for an interview in 2013 she said:

It was done with the first craftsman I worked with, Señor Abad. He did the Bottle pendant too. I was so thin at the time, and I was designing it on my left wrist. Then there was a flash between us about the area around the wrist bone. Between the craftsman and me, there is something in the air.

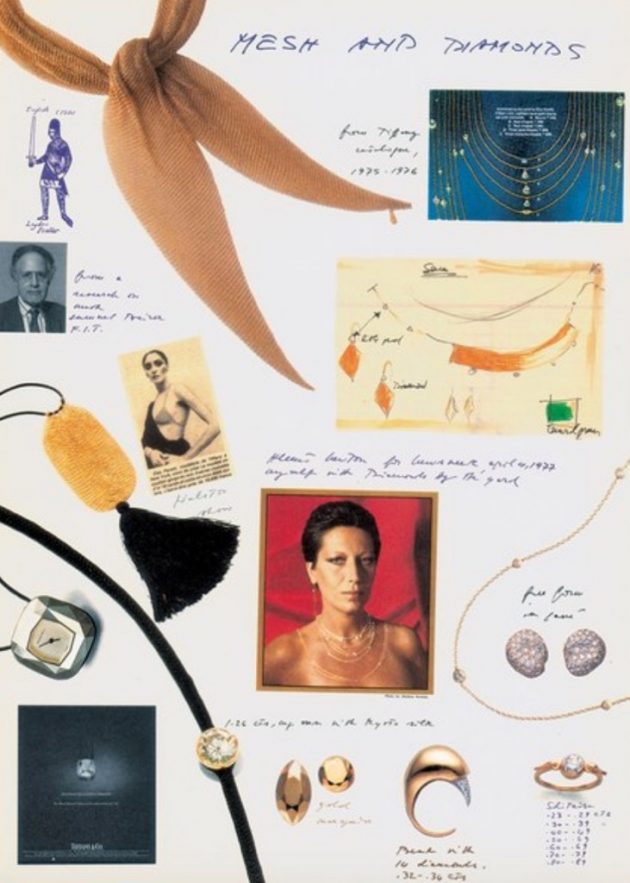

Page from, Fifteen of My Fifty With Tiffany, the Elsa Peretti-FIT retrospective catalogue showing her mesh scarf and Diamonds by the Yard. The man on the left side inset image is Sam Bizer from FIT, the instructor who helped Elsa figure out how to manufacture Mesh in New York City. Photo via

Elsa got the idea for her Mesh collection, which debuted in 1975, when she saw the material during a trip to India. Elsa’s problem was how to make mesh in Manhattan. She contacted the Director of the Jewelry Department at FIT, Samuel Beizer, to see if he could help her figure it out.

Together, they found old machines that were originally used to manufacture the pressure metal mesh for evening bags in the early years of the 20th century. Elsa and Sam used these apparatuses to make Mesh pieces including the bra that debuted on the Halston runway. The construction was such that there were no seams on the many links. It was smooth to the touch.

Elsa also introduced materials and production that were outside the routine materials used by Tiffany in fine jewelry. When I asked her if it was difficult to convince Tiffany to make her signature lacquer and hardwood bangles, Elsa said. “I am a bull. I am Taurus. My will is awful. If I like something, there is nothing else. I was a pain in the neck. I still am a pain in the neck.”

Elsa Peretti handle for disposable razors were inspired by the new Gillette disposable razors that were introduced in 1976. She said, “I wanted the name Gillette written in my catalogue. It was a big discussion. I considered the design prêt-à-porter.” Photo by Hiro via Instagram @elsaperettiofficial

Compared to her infamous disco days in New York City during the 1970s, Elsa spent the majority of the rest of her life quietly at various homes she had throughout Europe. Mainly she could be found in her beloved home in the small Catalan village of Sant Martí Vell.

From her perch in Spain, I heard through various friends how she not only became a philanthropist giving away millions through her Nando and Peretti Foundation, she also stayed on top of the jewelry and fashion news in New York City. She was a faithful phone caller and enjoyed Instagram. She sent word to some editors who celebrated the 50th anniversary of her Bone Cuff on the social media app about how much she enjoyed their posts.

Elsa walking with her dog Gina at the Santuari de nostra Señora de los Angeles in Sant Martí Vell, August 2016. Photo via Instagram @elsaperettiofficial

When my new book Beautiful Creatures was published featuring one of her starfish, a mutual friend of ours immediately sent her the pages with her jewel and the text on her story. Elsa told him to tell me she loved it and was buying several copies.

Whenever I spoke with Elsa she was as enthusiastic to tell her story as a young jewelry designer getting their first bit of coverage. She wanted to make sure I got the story right. Elsa was concerned about her legacy. Based on the outpouring of admiration for her work and the countless contemporary designers who cited her as a source of inspiration, I think her legend will only grow as time goes by.

Related Stories:

Elsa Peretti’s Story Told in Scrapbook Style

Elsa Peretti’s Iconic Bone Cuffs Reimagined

How Instagram Memorialized Elsa Peretti

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER