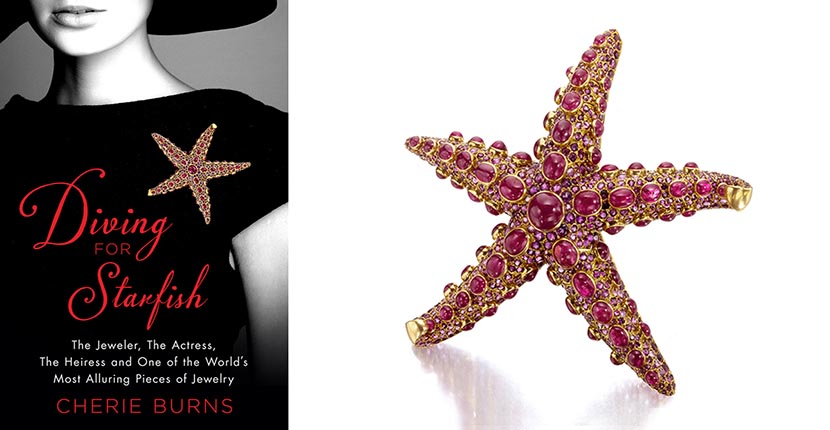

Diving For Starfish book jacket and Claudette Colbert's starfish brooch by Boivin from Siegelson Photo courtesy and Siegelson

Books & Exhibitions

Diving in Murky Waters for Boivin Starfish

‘One of the World’s Most Alluring Pieces of Jewelry’ remains a bit of a mystery

A few years ago when I first heard Cherie Burns, the author of a Millicent Rogers biography, was writing a book about the starfish brooches created by Boivin in the 1930s, I thought it was a pretty slender topic. I felt it would be a stretch for someone to fill 200-pages on the design. I believed they would need to speak French, have access to the Boivin archives and a talent for research not to mention a solid understanding of jewelry history to put the piece in context. A self-proclaimed fine jewelry novice, Cherie had none of the above and used lots of tricky tactics to try and make her publication feel substantial not to mention scandalous.

Diving For Starfish: The Jeweler, the Actress, the Heiress and One of the World’s Most Alluring Pieces of Jewelry is badly constructed and excessively repetitive. There is only one chapter when Burns takes a real stab at history and she totally misses the mark. Errors are scattered throughout the book. Cherie cites the “Van Cleef tutti frutti” bracelets as a piece that “attracted well-known and often glamorous buyers whose names become associated with the designs.” Obviously, she meant Cartier Tutti Frutti. One notable contemporary blunder is when she calls the designer James de Givenchy, James Givenchy leaving the “de” off.

While you might be thinking that the story would focus on Boivin, the in-house designer of the jewel, Juliette Moutard, as well as the original owners of the pieces, it doesn’t. Starfish is mainly about the author’s fixation with who acquired the jewels after “the actress” Claudette Colbert and “the heiress” Millicent Rogers referenced in the subtitle. Almost the entire text is about how the jewels have changed hands in the contemporary market. Burns bounces around the jewelry world and tries to make it sound like a detective story, interviewing esteemed experts as well as random folks who have just seen one of the pieces and don’t have anything insightful to say. She writes about insignificant meetings as though they are a big deal to flesh out her cast of characters in the book.

There is little joy in this search for starfish owners. The general tone is that of a spoiled teenager who can’t understand why people won’t just open up their accounts, share their client lists and reveal how much pieces were bought and sold for. “What’s the harm in that?” she naively protests. When a dealer demurs, she thinks they are not being “transparent” or worse she shreds them in her text. She praises some questionable people who give her information that I wouldn’t have trusted.

She is ruthless in her physical descriptions of people’s appearance not to mention their office spaces. She tries to gin up theories that the jewelry world is all dark and secretive. Yet, the fact remains lots of people helped her in so many ways. She did not return the favors in kind. She freely writes about gossipy tidbits she is told without fact-checking the information. She makes grand generalizations about the jewelry industry based on remarks people make in passing.

Near the end of the book, she gains a secret source she calls “Deep Throat” who assists her in identifying the previously unknown owner of a third Boivin starfish from the thirties. Oddly enough, the tipster operates in almost the same manner as Bob Woodward’s famous informant in All the President’s Men. They didn’t meet in dark garages, but he or she wouldn’t confirm facts until Cherie figured them out first. Seems suspicious and more than a little hypocritical that she doesn’t reveal this source and expects the jewelry dealers to give out private information.

There are too many contradictory statements throughout the book to list, but one of her main points is to endlessly quibble over the description of a few starfish jewels that were made from authorized sources years after the originals. Burns wants to call these “fakes” or “reproductions” and, in a whiny tone, can’t understand why they are not labeled as such. At the same time, she doesn’t seem to comprehend why a starfish made at a later date doesn’t cause excitement at auction.

The answers are simple. A house that owns the drawings—Boivin, David Webb, Verdura, Tiffany’s Schlumberger to name but a few—have a legitimate right to make a jewel based on one of the designs. It’s not a copy. Of course, the later versions don’t hold the same magic and fetch the same high figures at auction. With the finite quantity of vintage available, however, I don’t think it is difficult to understand why jewelers would remake masterpieces.

Despite the fact that Cherie pushed aggressively, in the end she was not granted interviews with two key players in the story, Fred Leighton aka Murray Mondschein and Natalie Hocq, the current owner of the Boivin brand. I am far from a key player, but I didn’t grant the author an interview either. I found her combative approach offsetting. I told her the little I knew about the starfish I had published in my book Bejeweled. In an exchange of a few emails, she didn’t seem to believe me. I found out in the book, Cherie thought a lot people were not telling her the full truth. Perhaps, it was just not what she wanted to hear. In the end she alienated a lot of the dealers who had originally helped her. She mentions this, but doesn’t quite say why.

Parts of the book I did enjoy were the surprisingly few moments when Cherie wrote interesting anecdotes about Millicent Rogers. It was also great when she shared details about what attracted a few of the dealers to jewelry. “It’s a passion,” Russell Zelenetz of Stephen Russell explained. “You can’t think of it strictly as a business.”

When Lee Siegelson, who bought and sold the Millicent Rogers starfish, told Burns he later saw it on a woman at a reception, she grilled him about who it might have been. He didn’t honestly know but he “sincerely said, ‘It was wonderful to see it again.’” For many of us in the field, it’s easy to understand that jewelry joy. It’s a shame Cherie was too cynical to realize the point of fascination about the Boivin starfish is not where jewels have gone in recent years. The design of the jewels, the people who made them, the context in which they were made and the original clientele are the heart of any great jewelry story. In the case of the Boivin starfish, unfortunately many of those details still remain a mystery.

Related Stories:

Joan Fontaine’s Verdura Jewelry in ‘Suspicion’

The Story Behind Jackie Kennedy’s Moon Earrings

The Mystery of Maria Félix’s Jewels

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER