From 'Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity,' a Cartier London turquoise tiara made in 1936; Cartier Paris turquoise, lapis and gold cigarette case made in 1930. Photo Cartier Collection © Cartier

Books & Exhibitions

The Link Between Cartier Style and Islamic Art

A new exhibition shows how an Eastern sensibility inspired the French jeweler

October 29, 2021 (Updated May 13, 2022 from Dallas, Texas)—When I was doing research on Cartier a few years ago I was astonished to learn in Louis Cartier’s 1942 New York Times obituary, he was almost as well known for his collection of miniature Islamic paintings as the jewelry made under his direction. Mr. Cartier has long been considered the creative genius of the French firm during the glorious years when he ran the Paris flagship from around 1900 to 1932. To say his art collection ranked alongside the jewelry was quite a statement.

The exhibition Cartier & Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity, that was originally staged at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris last October and opens at the Dallas Art Museum tomorrow, puts Louis Cartier’s Islamic art collection in context of the period and shows just how much it meant to the Maison’s jewelry. There are over 400 jewels and objects in the exhibition from the Cartier Collection as well as private and public loans, masterpieces of Islamic art, drawings, books, photographs and Cartier archival documents that trace the origins of the jeweler’s interest in Eastern art motifs.

The Dallas Art Museum and Musée des Arts Décoratifs co-organized the exhibition with additional collaboration by the Musée du Louvre and the support of Cartier. The work of the various jewelry and Islamic arts scholars from these institutions covers the importance of Islamic art, and its influence on Cartier, in a way that has never been done in the past.

“Islamic art is probably the most influential on our style, because of the abstraction and geometry,” explained Pierre Rainero, Director of Image, Style and Heritage for Maison Cartier during a presentation here in Dallas. “The shapes were important, like founding elements.”

In the main essay of the catalogue, “Islamic Art ‘Revealed’ A Path Toward Modern Design,” the two co-authors, Musée des Arts Décoratifs curators Judith Hénon-Raynaud and Évelyne Possémé, explain how Islamic art landed in the West during the early years of the 20th century and how popular it became. There wasn’t one headline news-making moment like Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 that inspired an Egyptian revival in the arts.

The movement in Islamic art was more complex and perhaps part of the reason why the roots of the narrative haven’t been as well known. In essence the curators highlight how there was a “weakening of the Islamic empires” and strengthening of colonialism. After 600 years parts of the Ottoman Empire transformed into Turkey in 1922. Persia became known as Iran by 1935. During the unstable period leading up to these changes, a lot of art exited the countries. The majority landed in Paris.

Photo Cartier Collection © Nils Herrmann and © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski

Louis Cartier was not the only jeweler who became enchanted with the lavishly detailed work characterized by lyrical lines and repetitive geometric forms. Henri Vever, one of the greatest jewelers of the era, assembled a legendary collection of Islamic art that was acquired by the Smithsonian in 1986. Both jewelers contributed works to a landmark 1912 exhibition of 500 Persian miniatures at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

The styles seen in the miniatures as well as other exhibitions in Europe inspired arts ranging from fashion to typography, interior design, theatre productions and books. A Thousand and One Nights, with Orientalist style illustrations by Léon Carré, became a best-seller. The Ballets Russes caused a sensation with their production of Scheherazade with costumes by Léon Bakst.

And then, of course, there were the Cartier creations.

Photo Cartier Paris Archives © Cartier

Louis Cartier guided his design team, including the great designer Charles Jacqeau, by supplying them with Islamic art reference books. He also provided them with some actual Islamic art, that is referred to as apprêts consistently throughout the catalogue. (The word means “primer.” I believe it is being used in the sense of introduction to a subject.)

This design process aligns with the methodology of many serious jewelry designers to this day. They begin by studying art, often in museums. They are not analyzing the works to copy them. They are taking cues and absorbing an essence.

the Musée des Arts Décoratifs show diamond and platinum jewelry from the early years of the 20th century with details inspired by Islamic art.

Photo Christophe Dellières

Some of the diamond and platinum jewels made by Cartier in the early years of the 20th century show a subtle Islamic influence. While most jewelers were still using a traditional code of royal motifs—bows, wreathes and flowers—Cartier began employing geometric forms found in Islamic art. It was ultimately their path into the geometry of Art Deco jewelry and modernity.

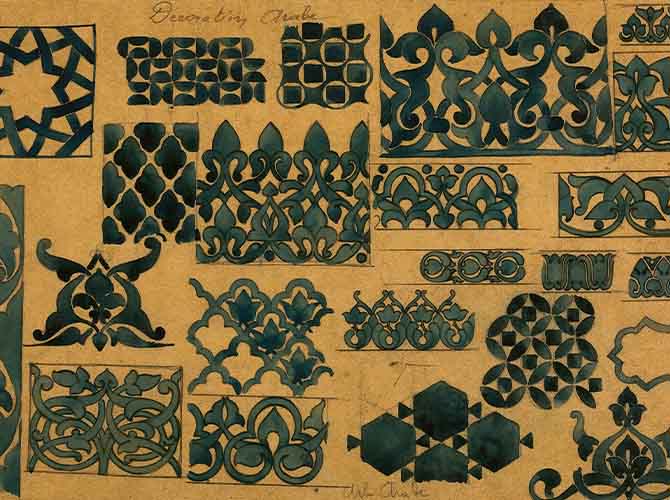

In one of the catalogue’s essays, the Dallas Museum’s Curator of Islamic and Medieval Art, Heather Ecker, identifies “Cartier’s Lexicon of Forms, adapted from Islamic Art and Architecture.” They include “simple and interlocking geometric shapes, palmette finials as singular or reciprocal forms, medallions and corner pieces, cartouches, the cloud collar, vine-scrolls, amulet shapes, the stepped merlon, different types of arcades, cypress trees, lotus blossoms, and çintamani patterns.”

By the 1920s and into the 1930s more of a literal link was made to Eastern cultures in the arts. For Cartier it translated into some beautiful objects and tiaras. One example is a “Persian” pattern in enamel on a gold vanity case made in 1924. The silhouette and gems in a Cartier London diamond tiara with paisley shaped turquoise. And the paisley diamond and platinum centerpiece of an aigrette.

While the main revelations of the exhibit and catalogue relate to Islamic art, there is also a glorious section devoted to how Indian jewels inspired Cartier’s work. It includes interesting information I had never come across before such as the fact that Cartier sold vintage Indian and Islamic jewelry in their inventory. Several pieces they had are featured in the publication.

the Musée des Arts Décoratifs show necklaces, earrings and brooches inspired by Indian jewelry and some with segments of actual Indian jewels incorporated into Cartier designs. Photo Christophe Dellières

One chapter in the exhibition catalogue I found particularly enlightening was written by Judith Hénon-Raynaud, Curator and Deputy Director of the Department of Islamic Art at the Musée du Louvre. The curator reviews what happened to Louis Cartier’s Islamic art collection. The jeweler loaned his pieces to several museum exhibits over the years. He didn’t do so to add to the provenance with the intention of selling them later during his life, but clearly because he loved the work and wanted to share it.

After Louis Cartier died in New York in 1942, some of the collection was sold by his heirs to the Harvard Art Museum which loaned pieces to this exhibition. Some of it was lost after being stored in England during World War II. All of it clearly lives on in spirit in the Cartier creations on display in Cartier & Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity.

Related Stories:

Pierre Cartier Was A Visionary Deal Broker

The Man Who Bartered His Mansion For Cartier Pearls

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER