Art Deco diamond and platinum bracelet made in France Photo courtesy of Kentshire

Jewelry History

A Few Facts Ignite an Author’s Imagination

M.J. Rose imagines the story of a French jeweler who made an Art Deco bracelet

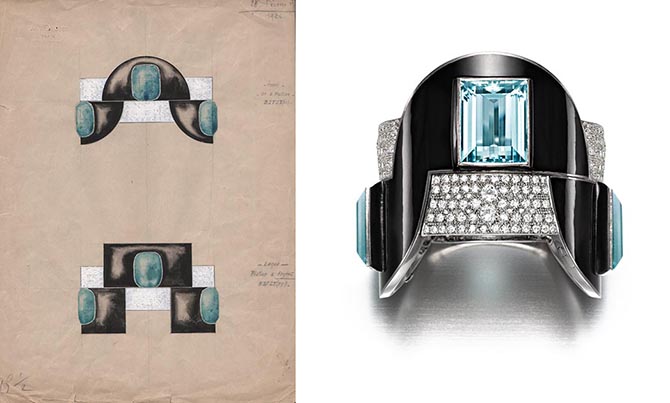

This description of an Art Deco diamond plaque bracelet, French import by Kentshire is all that is officially known about the design:

An Art Deco diamond bracelet comprised of eleven polished plaques, each centering on a collet-set, graduated old-mine diamond, with diamond hinges and flanked embellishment, in platinum. French import marks. Atw larger single stones: 10cts. Respective weights from flanged end: .60ct., 1.0ct., 1.0ct., 1.25cts., 1.15cts., 1.10cts., 1.0ct., 1.0ct., .65ct., .65ct., .60ct. Atw all stones 13.5 cts. 7″ inner circumference when clasped, 1/2″ wide

* * *

Until one day in April of 1925, Victor W. never loved a single piece of jewelry he’d toiled over. He also knew that no one at the prestigious house on Place Vendôme where he was apprenticed, cared that he had no connection to his work.

But he did care. Victor felt a yearning to create something different. To push the boundaries of the styles that belonged to the generations that came before him—styles no different than those his father and his father’s father had produced.

There had never been any doubt that Victor would follow in their footsteps. Yet, sitting at the bench, he questioned his decision to do so. Maybe there was a reason he felt nothing about his efforts. Maybe he wasn’t really suited to becoming a jeweler even though it was in his blood.

He never voiced his feelings, not to his father, not to the other apprentices nor the master jewelers in the shop. What would he say exactly? These designs bore me? They aren’t artful anymore. We’re just recreating the past over and over.

And then everything changed when an exhibit opened in April that revolutionized the world of design and Victor’s place in it. For seven months, the young jeweler spent whatever free time he had visiting The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (Exposition international des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes). He, along with 16 million other people, explored its pavilions, marveling at the displays that pushed style onto a brand-new path.

In the aftermath of World War I and the devastating losses France had endured, the event had been created by the French government to encourage people to look forward to the future. The idea was to highlight the most innovative and avant-garde work in all the decorative arts—architecture, interior decoration, furniture, glass, jewelry— from whence eventually, many years later came the word, Art Deco.

And the government’s plans succeeded on every level.

Week after week, Victor explored the Exposition that stretched from the Esplanade des Invalides across the Pont Alexandre III to the entrances of the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais. Fifty-seven acres in total.

He was learning a new language as he examined the pieces that, in order to have been accepted, had to be exclusively modern. No design could be based on any historical style. With every visit, he felt his eyes open wider and his imagination fly higher.

Without being aware of it, he was being liberated to develop his own style. Studying works by Ruhlmann, Legrain, Brandt, Dunard, Jallot, Rousseau, Sue et Mare, Gray, Lalique and Le Corbusier, Victor became enamored of the straight line, the circle, the idea of a design being clean and pure and unencumbered by frivolity.

At night, he lay in bed and imagined pieces eschewing overly embellished and complicated designs of the past and jewelry that instead followed the elements of this new style. He drew them in his mind and then finally began to sketch them, eventually expressing his newfound sensibility with gouache on paper.

But it would take three years until anyone saw a single one of those hundred drawings.

In the fall of 1928, on a chilly Wednesday afternoon, a wealthy industrialist visited the shop along with his young wife. It was their wedding anniversary he invited her to pick out something she liked.

“Anything, at all,” he said.

For the next two hours, no matter what the manager showed Madame L., nothing appealed to her.

It was all too fussy she said in a soft voice that drifted, along with the faint scent of her lilac and patchouli perfume, into the workshop where Victor sat working on a gold rope bracelet.

“Too old fashioned,” Victor heard her say. “Too much like what my mother would wear. I want something modern, to go with my newly bobbed hair and these shorter chemises Madame Chanel makes for me.”

The manager insisted the shop would create something to meet her specifications. They would have designs to show the couple in a matter of weeks and invited them to return.

For the first time, the house opened a competition among its jewelers to create a piece that would appeal to the young wife.

Victor, who was still an apprentice was not invited to submit drawings. But on the day they were due, he stealthily slipped one of his gouaches in among the others on the manager’s desk.

The following day, when the sketches were shown to Monsieur and Madame, Victor stood in the shadow of the workroom, listening as Madame commented.

Her voice was subdued but Victor picked up on every nuance of her disinterest.

“Not really what I imagined…. hmmmm…. Not this one either…. perhaps this but not really…”

Once again nothing seemed to strike Madame’s fancy. Victor counted down as he heard each sheet of paper rustle as she turned them. There were ten drawings including his.

She’d viewed six.

Then seven.

The eighth was turned over and then there was a moment of silence.

Madame uttered a small Oh. “This one,” she said in an awed voice. “This one is perfect.”

After Monsieur and Madame left, the manager entered into the workshop. In his hand was a single sheet of the thick gray stock the house used to illustrate their designs. He held it up.

“Whose work is this?” he asked. “I never saw it when I went over the studies yesterday and when Madame chose it, I was caught completely off guard.”

His face was stern as he looked at the three designers, waiting for them to respond.

The first shook his head.

“Not mine.”

The second shrugged his shoulders. “Nor mine.”

“I didn’t have anything to do with it,” said the third.

Victor knew the time had come for him to step forward to claim his work. He wondered if he’d be fired.

“It’s my design,” he said.

Victor never met the woman who wore his bracelet, but for years to come he would always remember the sound of her voice as she uttered that astonished Oh and the faint scent of lilacs and patchouli that she left behind, lingering on the air. He thought of her often, silently thanking her for changing the trajectory of his career.

M.J. Rose is a New York Times bestselling author; her most recent novel, The Last Tiara (February 2, 2021) has been hailed by Publishers Weekly as: “Engrossing… A wonderfully twisty plot that keeps the reader wanting to know more… [a] winning story.”

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER