The Manhattan delegation of a Woman Suffrage Party parade through New York in 1915. Photo Getty

Jewelry History

The Gold Wreath of a New York Suffragist

Please don’t call Vira Boarman Whitehouse’s jewel a crown

Originally published November 6, 2018—“Get out and vote!” has been the rallying cry from concerned citizens in advance of the critical mid-term elections. It’s astonishing how the privilege to cast a ballot needs to be promoted so heavily, especially when you consider how hard women fought for the right to vote in America. The battle began during the Civil War era and lasted around 72-years. Women were only granted voting rights throughout the country with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. (The fight went on for many more decades in some states where Black women were still disenfranchised.)

One of the heroines of suffragist movement in New York was Vira Boarman Whitehouse and there is a major jewel involved in her story. Born in New Orleans on September 16, 1875, Vira married New York stockbroker James Norman de Rapelye Whitehouse in 1898, had a daughter and did social work at Bellevue Hospital. Vira became woke to the cause after the Woman’s Suffrage Parade in 1913. Staged one day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in Washington, D.C., the event became violet. Over 100 women had to be hospitalized after they were attacked and police did little to help them.

Vira Boarman Whitehouse making a public speech for Women’s Suffrage on the streets of New York in December 1913. Photo via Wikipedia Commons

Once Vira joined the movement, she proved to be a visionary, a great organizer and a natural leader. Vira and her friend Helen Rogers Reid took over an empty Fifth Avenue shop for suffrage meetings. Vira marched at events, volunteered in the Women’s Union and gave her first public speech by the end of 1913. She was among the pioneers in cold calling and polling over the telephone. She donated money to the cause and led successful fundraising campaigns. With all her good works, it wasn’t long before Vira became chairman of the New York State’s Women’s Suffrage Party. When New York adopted women’s suffrage in 1917—which was considered a huge long shot—Vira was credited with making what seemed impossible happen.

In celebration of the win, the New York State Women’s Suffrage Party presented Vira with an 18K gold laurel wreath diadem that reportedly cost $1,000 at the time. The heavy piece was inscribed “To Vira Boarman Whitehouse from the women of New York State who she led to victory November 8, 1917.”

Much in the same way there is controversy around every little detail of politics today, there were issues surrounding the jewel. One bit of trouble came when a New York Times reporter mistakenly wrote that Vira had been “crowned” with the diadem when she gave something of a victory speech at Poli’s Theater in Washington. The reporter had arrived late and saw Vira wearing the piece and just assumed she had received it at the event. It was fake news. She had been given the jewel privately. The reporter also had some misinformation about the inscription leading to the confusion.

The laurel wreath diadem Vira Boarman received after leading New York’s suffrage movement to victory in 1917. Photo David Behl

In the correction published by the Times on December 23, 1917, the reporter couldn’t help but make a dig about the fact that the suffragists found the word “crown,” used in the original story, objectionable and wanted to be certain it was referred to as a “wreath.” Clearly, the women didn’t want monarchist connotations to surround the jewel. The Times felt compelled to write, by definition from the dictionary a crown is “a wreath or garland, or ornamental filet encircling the head, especially as a reward of victory or mark of honorable distinction.” Seriously, the tone just sounds like sour grapes from a journalist who had to make a correction.

Yet there were other issues with the jewel. Vera wrote a letter to the head of the gift committee—that the Times got its hands on—saying if she had known about the jewel, she would have stopped the purchase of the piece, but since it was already created she accepted it with “the greatest gratitude.”

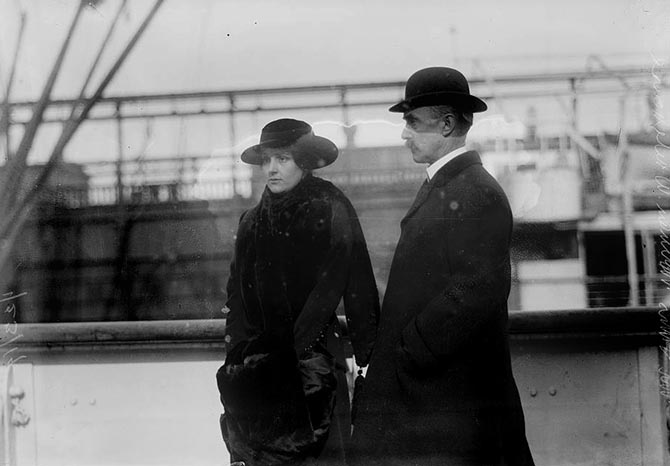

Vera Boarman Whitehouse with her husband James who was the treasurer of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. Photo Wikipedia Commons

There were also women on the committee who felt the money could have been spent more usefully in other areas. In the book Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York the authors Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello explain how Wreath-gate (my term, not theirs) revealed, “both the underlying class tensions and conflicting interpretations of democracy.” Ultimately, the authors land on the side of the gift pointing out, “Although the cost of the wreath may have seemed extravagant to some, it symbolizes the vast sums of money suffragists could raise during their campaign. It also emphasizes their generosity and heartfelt devotion to the cause and its leadership. Without a mastery of civics combined with theatrical skill, attaining the goal of suffrage may have been delayed even further.”

I had the opportunity to study Vira’s golden victory wreath some years ago when it was in the collection of Ralph Esmerian who over time had generously loaned it to at least one exhibition. Now the piece has disappeared into a private collection. I wish the owner would bring it back into public view as a symbol of women’s right to vote. If nothing else the story of struggle and a hard-won victory it represents should inspired everyone to cast a ballot.

Related Stories:

The MET Exhibit Asks: What Is Jewelry?

A Look At Jewelry Made For A Better Tomorrow

The True Story of Chris Evert’s Tennis Bracelet

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER