Portrait of Empress Eugénie by Franz Xaver Winterhalter and a diamond bow brooch by Kramer from her collection Photo of the jewel Christie's

Jewelry History Royalty

When and Why the French Sold the Crown Jewels

They feared the power of the treasures

In 1887 treasures that had once been the exclusive property of French kings and queens became available to the highest bidders. Purposely overlooking the historical significance of the collection, the Third Republic government built a case to get rid of the jewels by labeling them frivolous. A deputy proclaimed from the corridors of power, “A democracy that is sure of itself and confident in the future has a duty to rid itself of these objects of luxury, devoid of usefulness and moral worth.”

Portrait of Empress Eugénie by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1853

The truth behind the government’s outrage was actually something else entirely. The Third Republic had come into power in 1871 after the fall of Napolean III with only a slight margin of victory. Republicans lived in constant fear of a monarchist restoration by either Bourbons, Orleanists or Bonapartists. They believed anybody whose family had worn the jewels might suddenly claim to them and the political power they represent if they remained in the French treasury.

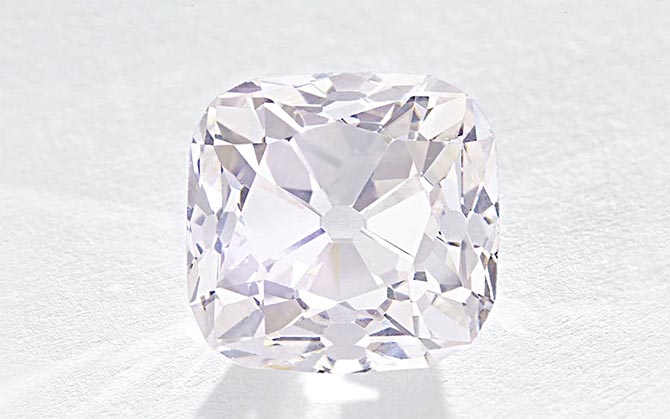

Certainly, the history of the collection was a powerful symbol of the monarchy. In 1525, François I had established the French Crown Jewels after being forced to hand over his own jewels as ransom during an Italian campaign. Subsequent kings added to the holdings. Louis XIV acquired many large diamonds including the 19.07-carat light pink Grand Mazarin.

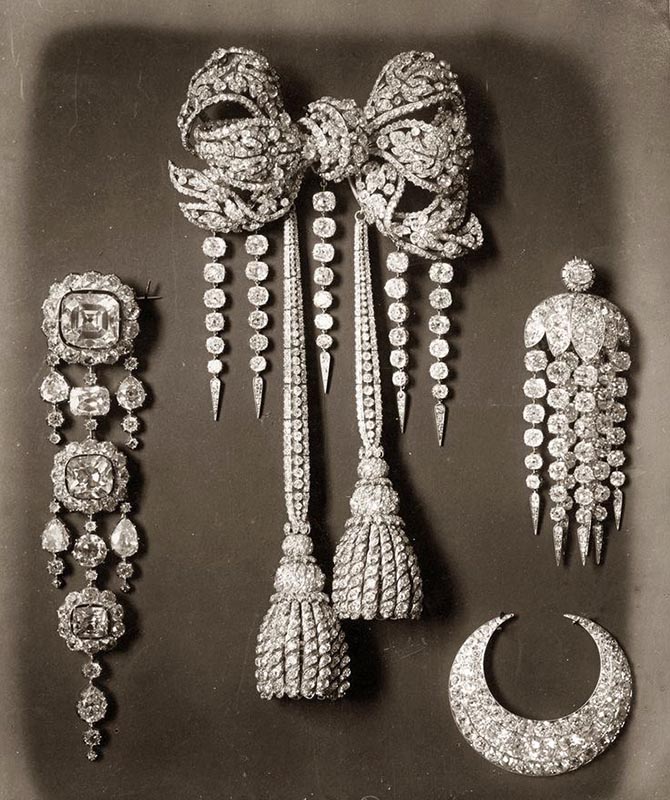

The last person to put an imprint on the French Crown Jewels was the chic Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III. She had several pieces from the collection dismantled and then presented the gems to master jewelers. The creations made for Eugénie with the stones featured an array of bows, stars, crescents, flowers and neo-classical motifs. It was a dazzling blend of what the empress admired in the historic jewels of her predecessors and the most fashionable contemporary styles.

The light pink 19.07-carat Grand Mazarin diamond from the French Crown Jewels Photo Christie’s

When the government made the decision to sell their masterpieces and the nation’s treasury of important gems, French jewelers were outranged. In response, the Third Republic agreed to set aside a small group of items to be held in perpetuity by the state. The 140.64-carat Regent diamond was one gem they decided to keep. It had been purchased by Louis XV. Napoleon had underwritten the cost of his army by pledging the Regent to an Amsterdam banker. After his victory he considered the diamond a good-luck charm and wore it in the hilt of his sword. From Eugénie’s collection one brooch set with two Mazarin diamonds was preserved. Everything the government kept was housed in the Museum of Natural History or the Louvre.

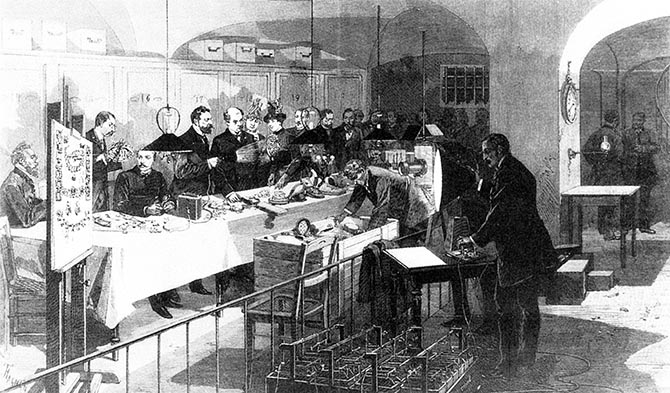

While pacifying the jewelers with this gesture, the government made another decision that outraged the trade all over again. They broke apart many jewels to sell as segments as well as loose gems. Next, the government began a blitz of promotion. A photographer named Berthaud was hired to shoot the collection for a catalogue which was sent to prospective bidders—diamond dealers, importers and jewelers—around the world. Pictures were also given to the press. The French publication L’Illustration even featured behind-the-scenes shots of Berthaud’s photography session at the Ministry of Finance.

Behind the scenes image of the French Crown Jewels being catalogued for the sale.

As soon as the catalogues were distributed, jewelers started making look alikes. The American trade publication, Jewelers’ Circular reported that Alfred H. Smith & Co., a New York diamond importer, had a copy of the catalogue and “cordially invited their friends and patrons to call and examine them.” It was code language to commission their own version of the jewels.

When the nine-session auction finally began in the state rooms of the Louvre on May 12, 1887 the worst fears of the Third Republic were confirmed. The Orleanists, members of the French royal family, showed up to bid on what they considered their legacy. Ultimately, however, they were unable to compete with a formidable cross section of jewelers eager to purchase the goods for their clients.

Page from the catalogue of the French Crown Jewels

An up-and-coming jeweler named Frédéric Boucheron won the Grand Mazarin. Empress Eugénie’s favorite jeweler, Bapst, had the highest bid for tiara with a Greek key pattern they had made in 1864. A jeweler representing the British royal family swept up a piece made by Bapst in 1868.

The dark horse of the auction was the American jeweler Tiffany who ultimately carried off more than two thirds of the merchandise, purchasing hundreds of years of history in an instant. Tiffany sold its prizes in specially made leather boxes embossed “Diamants de la Couronne” in gold on the top and “Tiffany & Co. New York and Paris” on the satin of the inner lid, tidily packaging the history.

Empress Eugénie’s Diamond Bow Brooch and the special box created for the jewel (shown out of scale). Photo Christie’s

Only a few of the jewels have appeared publicly in the 131-years since the sale of the French Crown Jewels. During the 1930s, a piece of Eugénie’s currant leaf bodice decoration surfaced on the market at Paul Flato’s establishment in New York. The oxidized silver jewel was dipped in platinum to match contemporary styles for formal jewelry and gifted, on behalf of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, to the opera singer Lucrezia Bori when she retired. Bori returned the brooch to the institution in her bequest where it was on display during the season for decades. In 2014, the MET made the decision to deaccession the treasure. It was sold at Christie’s for $2.3-million to a private collector.

All of Empress Eugénie’s currant leaf corsage ornaments shown in the original sale catalogue of the French Crown Jewels and the segment sold at Christie’s in 2014 by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Photo Christie’s

In 2008, when Empress Eugénie’s diamond bow brooch by Kramer, that had been purchased by a jeweler, Emile Schlesinger on behalf of Mrs. Caroline Astor, became available through Christie’s, the Friends of the Louvre organization paid almost $11-million for the jewel. It is currently on display at the museum with other pieces from the collection.

The dreamy light pink 19.07-carat Grand Mazarin resurfaced in the public arena just last fall. In the November, 2017 sale at Christie’s in Geneva the gem sold for just over $14-million. It’s current whereabouts are publicly unknown. Watch the video on the history of the piece here.

Related Stories:

Henry VIII’s Favorite Jewelry Designer

Art Deco Objects From a Royal Collection

The Magnificence of India on Display at the Grand Palais

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER