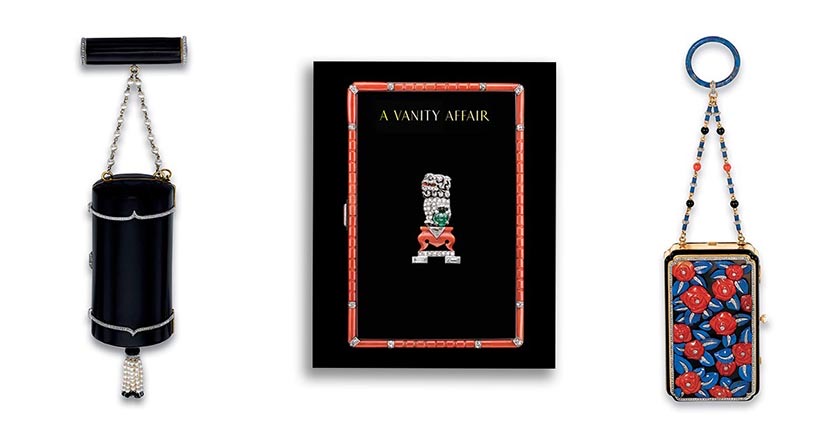

A Cartier black enamel Art Deco vanity case, the cover of ‘Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire’and the Poiret Rose coral lapis and enamel Art Deco vanity case by Lacloche Frères Photo Rizzoli

Books & Exhibitions

A Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire

The book reviews bejeweled objects from glamorous days gone by

“Some might think that they are fashion accessories; some would say that they are technical marvels; some could say that they are pieces of history; others that they are bejeweled art. They are indeed all of the above. As ultimately everything is interlinked is it not? History, way of life, architecture, artistic movements, fashion trends, they all influence one another. Jewelry and in particular the art of necessaire, is no exception being a mirror of all these influences.”—A Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire

The lusciously illustrated Rizzoli book, A Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire, explores one couple’s amazing collection of vanity cases from the 19th century and onwards. The volume is a brilliant history of objects d’art that offered both elegant and practical ways for a woman to carry cigarettes, lipstick, powder lighter, theater tickets, keys, pills — even perfume.

But why A Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire becomes a necessaire addition to every jewelry lover’s and collector’s library is that includes histories of jewelry, cosmetics and of women’s emancipation which all together help us understand why these vanity’s came into being and why they were so ingenious. It was written by Lyne Kaddoura with contribution from jewelry experts Pierre Rainero and Vivienne Becker an introduction by David Snowdon and preface by François Curiel.

Cut-cornered rectangular onyx case with an engraved Japanese landscape, decorated with a lapis lazuli and simulated turquoise jar with millegrain-set rose-cut diamond handles extending a blue enamel cherry blossom tree set with turquoise cabochon flowers with diamond pistils. Diamond-set shòu motif clasp and hinges. French assay mark and Strauss Allard Meyer. Photo © diode SA – Denis Hayoun

As the hundreds of photographs in the book illustrate, the “boxes” provided a worthy canvas for some of best work of Cartier, Van Cleef and Arpels, Boucheron, Lacloche Frères, and others. Designed not just to dazzle on the outside, the cases ingeniously provided room what a woman out for the evening required. And as such show off their creator’s artistry and ability to solve problems and come up with solutions.

While some called these objects the ultimate jeweled fashion accessories, the book does an excellent job of explaining and showing how completely functional and, yes, necessary, they were.

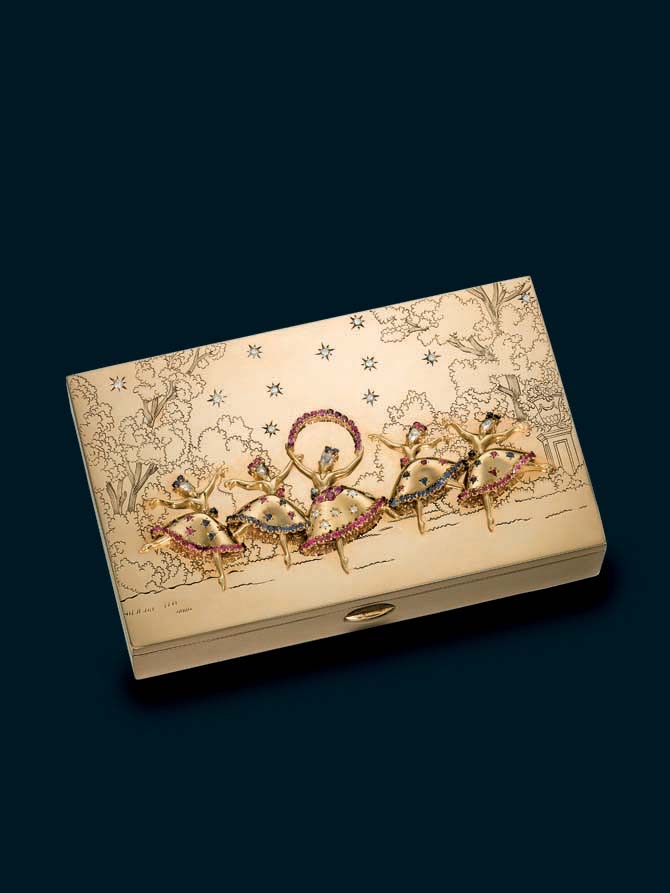

Gold, sapphire, ruby and diamond vanity case, by John Rubel & Co, circa 1943. John Rubel was a manufacturer who worked for Van Cleef & Arpels from around 1939 to 1943. Designer Maurice Duvalet who was responsible for the ballerinas was employed by both firms. Photo © diode SA – Denis Hayoun

A Vanity Affair: L’Art du Necessaire is a visual treat of objects made from precious metals, inlays of lacquer, gemstones, mother-of-pearl, jade, or enamel, and an intellectual treat exploring why these very special items are worthy of study and collection as object of fine craftsmanship’s, ingenuity and creativity. Each of the exceptionally well written essays gives insight into another aspect of how these necessaires came to be and why they are so worthy of both study and collection.

In Diana Scarisbrick’s essay about the history of cosmetics, she takes us back to the Nile Valley, in 3.500 B.C. to show how early our impulses to improve our looks resulted in items that are not that far from what the international cosmetic industry still produces.

Upright rectangular purple jade case of Japanese inspiration, with onyx and jade lid resembling a pagoda. Decorated with an inlaid black lacquer wisteria tree with carved amethyst flowers and diamond pistils, atop a jade and diamond lacquer wisteria tree with carved amethyst flowers and diamond pistils, atop a jade and diamond jar by Black, Starr & Frost, circa 1927 Photo © diode SA – Denis Hayoun

In another piece, Laurence Mouillefarine writes about Henri Clouzot, curator at the Musée Galliera who in the early 1920s, descried the Lacloche Frères cases for cosmetics, cigarettes and face powder as “tiny, charming knick-knacks that pretty fingers delight in handling, lending themselves to the daintiest gestures in the world.” And went on to point out that the French words for play and jewel, jeu and joyau have the same etymology and describe both the joy and function of these boxes so well.

Although the book is filled with photos and information about miniature pieces of art, the story it tells and the worlds it conjures are large, fascinating and very much worth examining. As one of the author’s sage points out, “For the majority of the cases, we may never know the name of their original owners, the name inscribed on these ivory plaques, which have been rubbed away with time. What remains is the beauty, the craftsmanship, these exquisite pieces of history.”

Related Stories:

The Amazing Work of Jewelry’s Designing Women

The Author Who Uses Real Jewels in Her Fiction

Diving In Murky Waters For Boivin Starfish

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER