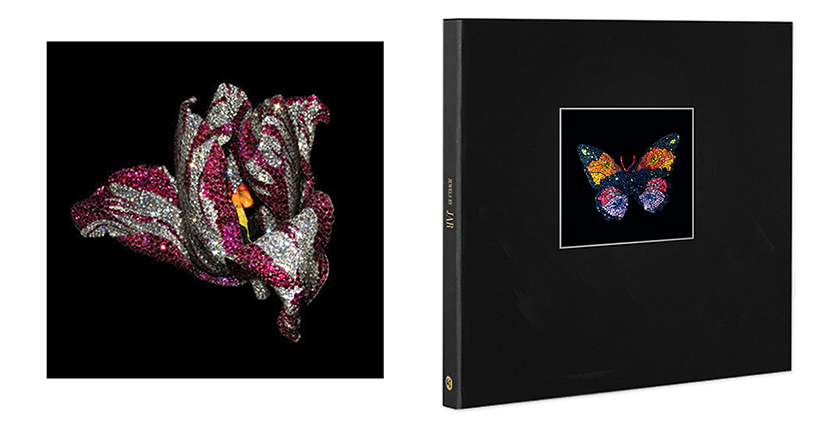

Ruby, diamond, pink sapphire, garnet, silver, gold and enamel tulip brooch, 2008 from the Jewels by Jar publication at right

Books & Exhibitions

A Jewel by JAR You Can and Must Get

The mini exhibition catalogue is a gem

November 1, 2017—When the Jewels by JAR exhibition opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013, amidst the overwhelming enthusiasm about the collection of almost 400 pieces by the elusive designer on display, there was a contrarian chorus bellowing about the lack of storyline in the presentation. Not one fact was listed about Joel Arthur Rosenthal’s biography, sources of inspiration or unique techniques. The museum’s free paper handout, given at the entrance to the exhibit, did little to illuminate the designer’s background. It only had a scant bio, elemental jewelry descriptions and a few of the owners names including Gwyneth Paltrow, Stephanie Seymour, Lily Safra and the Prince of Wales. The New York Times article “Jewelry Show At MET Raises Questions” reviewed the issue and quoted yours truly among others about the problem.

Emerald, pearl, diamond and platinum earrings, 2011 Photo from Jewels by Jar

The little catalogue for the Jewels by JAR exhibit with an introduction by the museum’s director Thomas Campbell added another layer of overall confusion. It wasn’t written by the curator, Jane Adlin, but a specialist in eighteenth-century Sèvres porcelain named Adrian Sasson. Despite it all, if you are a fan or just fascinated by the designer, I recommend getting the book.

The lovely little compendium provides an opportunity to linger over 65 of Rosenthal’s strongest works. Jewels by JAR is also by far the most affordable book on the designer at $28.75. The three other JAR publications range in price from $65 for the small 40-page paperback catalogue for the 2002 exhibit at Somerset House in London, The Jewels of JAR, Paris, to over $1,000 for the two massive books that are often referred to as JAR I and JAR II. Both weigh more than 10 pounds and feature hundreds of images of the designer’s work but no storyline. In all the books, everything is photographed on a black background. Clearly it is something the dictatorial designer prefers, perhaps thinking it highlights gems when in fact it does the opposite.

As for the text in Jewels by JAR, Sasson mainly tows the Rosenthal line that he prefers to allow the work to speak for itself. Frustrating. There are absolutely no elaborations on the designer’s sources of inspiration when it is clear Rosenthal is enchanted by eighteenth century jewelry, turn of the century creations of Boucheron and Indian jewels of the Mughal period as well as the twentieth century masters, Verdura and Belperron. Like so many others, Sasson writes about JAR as though the work exists in a vacuum. This angle might make a reader believe Rosenthal invented novel gem combinations that others had done before him. One example is the high-low diamond and wood mix seen in JAR jewels. Van Cleef & Arpels used wood and diamonds as far back as the 1930s.

What Sassoon does reveal is a glimpse into Rosenthal’s fascinating design process. Rosenthal sketched objects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a child, yet he does not create formal designs for any of his pieces. Instead, he doodles and shapes paper, uses a felt tip pen on silver models and practically plays a game of charades with his manufacturers to get his ideas across. Clearly the next work about JAR should be a documentary, recording what must be dynamic design sessions.

Related Stories:

See All 12 of Ann Getty’s Jewels By JAR

A Look Back at Ellen Barkin’s Jewelry

The Link Between Cartier Style and Islamic Art

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER