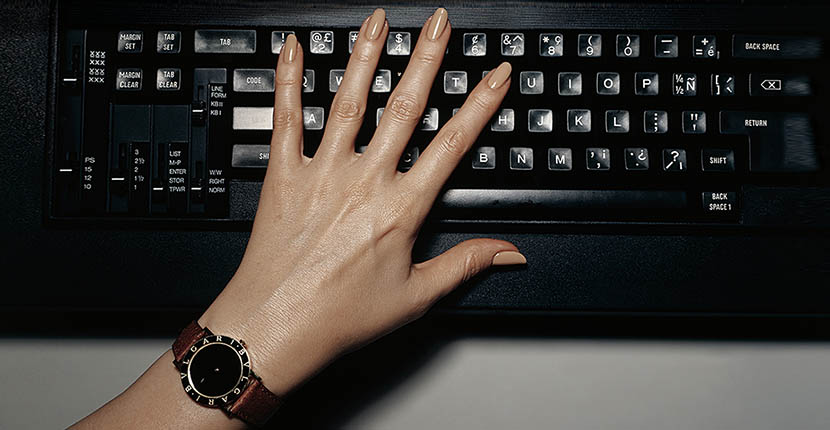

Bulgari-Bulgari watch and Olivetti ET231 typewriter in a 1981 image Irving Penn took for 'Vogue'

Jewelry History

An Ode to Photographer Irving Penn

In celebration of the MET’s Centennial exhibit of his work

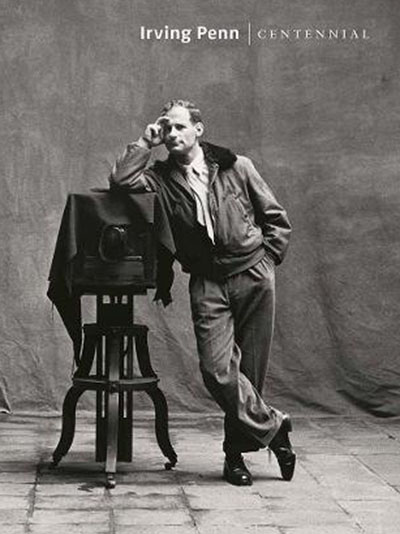

A self-portrait of Irving Penn is on the cover of the MET exhibition catalogue for ‘Centennial’

“A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart, leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it,” Irving Penn once explained. “It is, in a word, effective.”

The most comprehensive exhibition of Irving Penn’s photography is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It can also be found in the catalogue for the show.

Irving Penn: Centennial, that will remain open until July 30, 2017, mark’s the 100th year since the American photographer’s birth on June 16, 1917 in Plainfield, New Jersey. (He passed away on October 9, 2009.)

The presentation of over 200 photographs cover the phases of his long prolific career. The lead curator on the project Maria Morris Hambourg says in the background video for the show, “He could progress in his art because he had to work every day for sixty years. He would describe to me the moment when he was taking those pictures. He was so taken with what he was doing. He wanted to go on and on until, as he put it, ‘something godly would happened.’”

Something godly did happened in Penn’s photographs all the time. It happened when he was photographing celebrities in his studios or Quechua children in Cuzco, Peru. Penn’s cigarette studies are mesmerizing. His flowers are absolute poetry. He made working class heroes out of tradesmen in his images.

What is also amazing in the photographer’s epic oeuvre is his shots with gems, jewelry and watches. These accessories turned up on models and celebrities when they were being photographed by Penn for Vogue. His photo of Yves Saint Laurent makes the designer’s Cartier Tank watch part of the dynamic composition. The turtle ring in his Freckles image plays into the dignity of the portrait. Penn’s images focusing on jewels are among the best ever done.

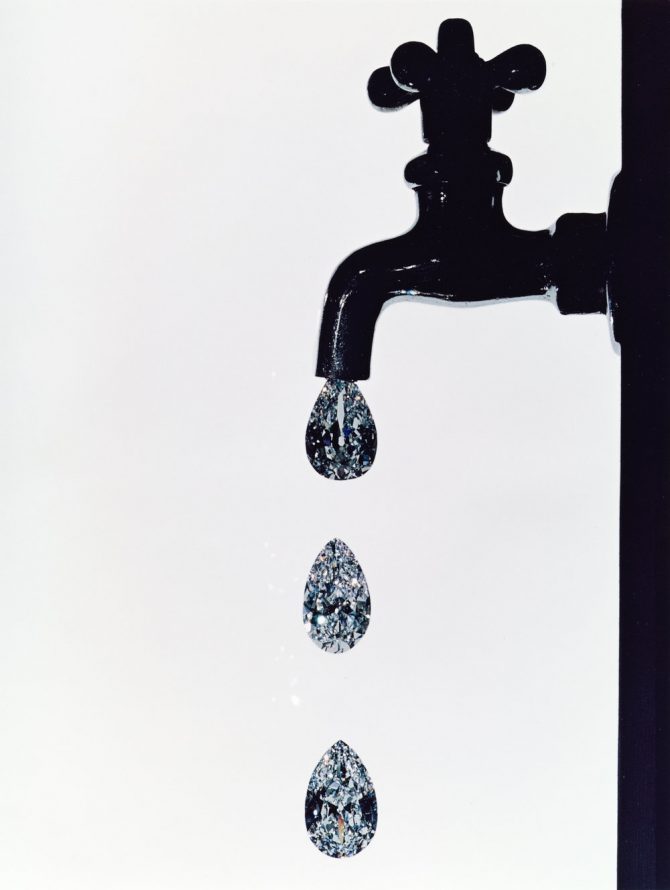

‘Faucet Dripping With Diamonds’ by Irving Penn

Penn’s most famous jewelry photo, Faucet Dripping With Diamonds, was published in his 1991 book Passage: A Work Record. In the text, he gave a little behind-the-scenes detail of the 1963 shot: “Diamond dealer Harry Winston found himself one day with three similar enormous pear-shaped diamonds in his New York inventory. We quickly set up a picture for Vogue right in Winston’s office, in that way saving time and making unnecessary the usual armed guards had we taken the picture in our own studio.”

In April, 1971 Penn took a picture of Bulgari’s amazing enamel snake bracelets and a belt coiled around a model’s hands. The shot has never been part of an Irving Penn exhibit, but it has been one of my favorites ever since I came across it while I was researching my book Bulgari: Serpenti Collection. The image was originally used in the magazine to illustrate an excerpt of Hortense Calisher’s novel Queenie titled “A 1971 Gigi Looks at Sex, a Way of Life, a Private Joy.” It’s my hunch the photo was Penn’s way of fulfilling editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland’s, September 1968 memo to her editorial staff that said:

Don’t forget the Serpent . . .

The serpent should be on every finger and all wrists and all everywhere . . .

The serpent is the motif of the hours in jewelry . . .

We cannot see enough of them . . .

Bulgari enamel, gold and gemset snakes in 1971 Irving Penn image

In 1981, Penn created a photo for a Vogue story about state-of-the-art Italian design showing a Bulgari-Bulgari watch on the wrist of a model’s hand resting over a black Olivetti ET231 typewriter (seen above). I was lucky enough to have the image featured in my book Bulgari-Bulgari Collection. Really, the shot is somewhat straightforward, a watch and a keyboard, but the photographer’s lighting made it sexy and timeless.

It’s clear from looking at his complete body of work, Penn was passionate about every photo he took whether it was his artistic, commercial or editorial work. The way he saw beauty in everything is expressed in one of his more well-known quotes, “Photographing a cake can be art.”

Similar Stories:

Verdura’s Historic Collab With Dali

Calder’s First Jewelry Exhibit in London

A Brief History of Elegant Hands in Jewelry

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER