Jewelry History

Part 1: Jewelry Gene, Jewels in the Blood Stream

Jubilant Jewelry History

Almost every woman has a jewelry gene. —Lesley Stahl, 60 Minutes correspondent

Editor’s note: This post, one of the first published on The Adventurine, is being reupped in celebration of our 5th anniversary.

June 1, 2016—You know when you have it. A jewelry gene decorates the top of your DNA structure like a tiara. It manifests itself as a passion for earrings, necklaces, bracelets and rings. You are quite simply dazzled by diamonds, awestruck by rubies, emeralds and sapphires. You can’t help but stop and shop for jewelry in boutiques when a little sparkle catches your eye. You are mesmerized by baubles on blogs and in the pages of fashion magazines. You save to get that certain something. Or you strategize on how to drop a clear hint about it to your loved one. You adore having it and holding it. You wouldn’t go out without wearing it. Whether it is a priceless treasure or a flea market find, jewelry is part of what makes you, well, you.

Above and beyond the obvious—acquiring and wearing—jewelry is one of your favorite intellectual pursuits. You have the gene and you are a bit of a jewelry genius. You are seriously interested in gemology. You might even have a monogrammed loupe in your purse just in case you have to check a mark or review the quality and craftsmanship of a jewel on the run. Your absolute favorite course of study is the history of jewelry.

If you are anything like us, and we suspect you are, an eat-breathe-sleep-jewelry-type, you plan travel around jewelry exhibitions and are always on the lookout for great new books covering the subject. You have dog-eared copies of the classics by the father of American gemology George Fredrick Kunz: The Curious Lore of Precious Gems, The Magic of Jewels and Charms and The Book of the Pearl.

You speak a smattering of French because it is the language of jewelry as well as love. After all, you need to understand key jewelry terms that have no English translation such as bijoux, minaudiére, sautoir, lavaliere, en tremblant and en suite. But that’s elementary, entry-level type of stuff. Jewelry history gets really interesting when you begin to connect the dots down the centuries, no—make that string the pearls—of the role of jewelry in, what shall we call it, the bigger picture.

One of our favorite examples is the story, the true story of Alexander the Great. It is commonly believed that the golden Greek traveled widely during the fourth century—when it was not exactly easy to get around—with his armies and entourage to conquer the world. We have a different theory on his travels. Alexander left home and went far and wide for gold. Check the map. His journeys took him close enough for comfort to virtually every gold mine in the eastern empire. Historians tend to focus on Alexander’s knack for civilizing cultures, his respect for writers, the immense library in Alexandria, his tutor Aristotle. These were fine fringe benefits to his travels, but look at the jewelry made with the gold Alexander sent home. It is the glory that was ancient Greece.

Fourth Century BC Greek Gold Earrings Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Historically, an important period for the jewelry inclined, is the Baroque. Not necessarily because of the ornate art or the uninhibited, okay, over-the-top architecture or even the magnificent music, the thrill of the strings. It is because the entire period, two centuries long, was named after a pearl. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, diamonds were all fine and good but the truth is, they were not as good as the pearl. Lapidaries did not know how to cut diamonds to reveal the gem’s full inner light. It was the pluck-it-out-of-the oyster drip-dry pearl that was the great jewelry prize. Seriously, getting them was a major hassle. Divers had to go deep into the ocean and gather up oysters with one big breath—no oxygen tanks. Then pray that when they pried them open, something gorgeous would tumble out. And if something did, it was like winning the lottery.

A late 16th century gold and enamel pendant with a baroque pearl centaur. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Royalty was crazy for pearls before, during, and after the Baroque period. When England ruled the waves, Queen Elizabeth I was rumored to sew them with her very own hands on her gowns and have them pinned in her elaborate hairdos. Mary Tudor had a lollapalooza of a pearl, the pear-shape 203.84 grain, La Peregrina. Translated, La Peregrina means The Wanderer—and wander it has. When Elizabeth died, the pearl wandered back to Spain in the pocket of Philip II. Velasquez painted Margarita of Austria, wife of the Philip III, wearing it. Napoleon’s brother, Joseph, took it when he took Spain. In 1969 La Peregrina appeared at auction in New York City. Richard Burton nabbed it for Elizabeth Taylor who gave the peripatetic pearl a home in Hollywood and wore it as part of her costumes in two movies. For Anne of a Thousand Days (1969) Burton was Henry VIII, Taylor played a teensy role as a Masked Courtesan dressed to the nines in the historic jewel on a simple pearl chain. Taylor showed off the historic marine gem again in the 1977 film A Little Night Music By the time of the movie Cartier had concocted an elaborate necklace for the pearl inspired by the piece Mary Tudor had it mounted in.

In 2011 when the Peregrina was put on the Christie’s auction block in New York with Taylor’s estate, the pearl not only sold for more than any other jewel in the collection it also presented one of the most entertaining segments of The Legendary Jewels portion of the proceedings as clients began screaming out their multi-million dollar bids to the eminent auctioneer Francois Curiel. Watch just how this moment went down here.

Now where were we? Back a few hundred years, in the eighteenth century jubilant jewelry history was interrupted because the French crown was about to crumble like a cookie. The blame falls squarely on the silky shoulders of Marie Antoinette. The queen did not help the monarchy when her recipe for the good life was leaked to the revolutionaries. You remember the let ‘em eat cake scenario. Anyway, considering the queen’s bad form and voracious appetite for showy diamonds, it is no wonder a detrimental rumor about a big time jewel made for the queen began to circulate like wildfire.

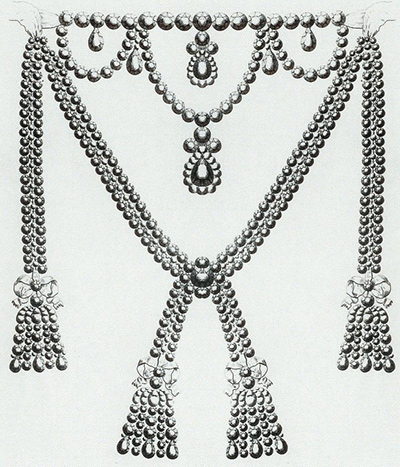

Antoinette was accused of raiding the French treasury for enough francs to buy the fringy necklace with tassels, swags and bows dripping in diamonds. The rumor implicated the queen, her personal secretary and the cardinal. Historians say it brought on the revolution and cost the queen her head. In her defense Antoinette denied the purchase all the way to the guillotine. She reputedly said, “France needs a ship more than another jewel.”

Engraving of the necklace that ignited the French revolution. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Truth be told, the necklace never did turn up in the crown collection but the legend has never died. There were drawings of the controversial extravagance detailing carat weights. A costume rendition has even had a couple of Hollywood close-ups. First, in the 1938 film Marie Antoinette with Norma Shearer in the title role the studio dubbed “Madame of Devil May Care.” Two years later the Marie Antoinette prop appeared in the screwball comedy Philadelphia Story among leading lady Katherine Hepburn’s lavish spread of wedding presents.

Virginia Weidler holding up the Marie Antoinette necklace prop in Philadelphia Story, (MGM).

Her little sister played by Virginia Weidler makes a real insider’s jewelry joke when she picks up the monstrous piece and says, “This stinks.”

Click here to read Part II of The Jewelry Gene and click here to read Part III of the Jewelry Gene

Related Stories:

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER