Belle Epoque crescent shaped emerald and diamond brooch formerly in the collection of Anita Delgado being sold at Christie's in New York. Photo Christie's

Jewelry News

Alluring Emeralds in the Al Thani Collection

A look at the gem in jewels from the Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence auction

Emeralds are among the most consistent decorative elements throughout the selection of The Al Thani Collection being sold at Christie’s in the Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence auction on June 19, 2019. To me these emerald focused creations have proven to be the most fascinating among all the 400 treasures in the auction.

Introduced to India by Spanish Conquistadors in the 16th and 17th centuries, Colombian emeralds were revered by the Mughal Emperors and not only for their inherent beauty. The verdant gems within Mughal jewelry symbolized the force of life: green as the flora created by the blue sky, combined with the yellow sun, while spinels and rubies represented blood, the life force of the animal kingdom. The more impressive the size and appearance of a gemstone, the greater a signifier it was of the wearer’s spiritual veneration to the gods.

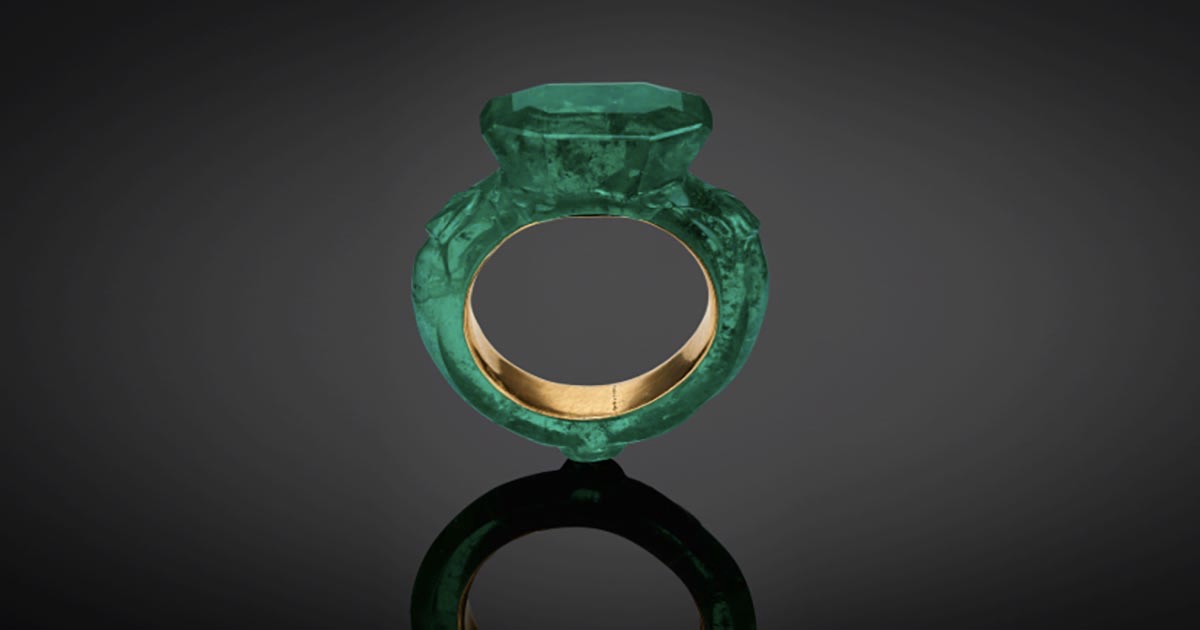

A 16th-17th Century carved emerald and gold ring from the Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence sale at Christie’s. Estimate $100,000 – $150,000 Photo Christie’s

One of the oldest pieces in the entire collection is without doubt one of the most phenomenal. The concise description courtesy of Christie’s reads: “Ring, India, sixteenth century. Emerald with gold sleeve.” One enormous, sole emerald carved into a ring, with only a sliver of gold acting as a hidden inner band between the royal wearer and the gemstone.

The age of the ring also belies the simplicity of its design, and simultaneously the standard of quality which is now completely unattainable. It is the only design which could not be emulated in the present day; because no matter how advanced our craftsmen and technology have become, the correlation between such an enormous size and high quality of emeralds simply no longer exists.

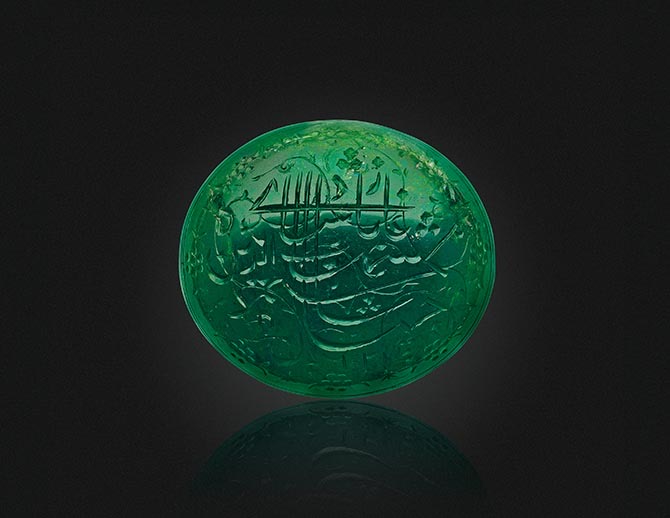

The 30.60-carat ‘Shah Jahan Emerald’ being sold at Christie’s in New York. Estimate $500,000 – $700,000 Photo Christie’s

Special reverence should be reserved for a gemstone presented without any decorative context, that has survived centuries with no superfluous addition. ‘The Shah Jahan Emerald‘ is said to have been carved, cut and polished in North India or Deccan, and is dated between 1621 and 1622. The emerald is not only a fundamental component of the collection because of its age and quality, but its inscription makes it wholly unique. The Mughal dynasty’s predecessors The Timurids began engraving titles on stones of outstanding quality; emeralds were usually inscribed with religious, whereas spinels and rubies would bare royal titles of their owners. Here though, the Shah Jahan Emerald reads “Shihab al-din Muhammad Shah Jahan Padshah Ghazi 1031,” in Persian.

An Art Deco Carved Emerald, Sapphire, Diamond and Pearl Aigrette by Paul Iribe for Robert Linzeler being sold at Christie’s in New York. Estimate $500,000 – $700,000 Photo Christie’s

Another favorite creation which showcases the beauty of the emerald is an aigrette made around the turn of the 20th century. The emerald itself is estimated to have been cut and carved between 1850 and 1900 in India. The spectacular design featuring sapphires, diamonds, pearls and platinum was conceived by the legendary Paul Iribe in Paris in 1910 for jeweler Robert Linzeler. Iribe’s experience in fashion illustration and of working on Hollywood films with the sensational director Cecil B. DeMille comes shining through in this piece. The jewel is a reflection of the Indian heritage for the adoration of gemstones and the dawn of a new era in European jewelry design as well as a little old Hollywood razzle-dazzle. This jewel displays a very early interpretation of the aesthetic principles of the Art Deco movement.

Aside from the show-stopping emerald pieces, the verdant stone is also present alongside spinels, rubies and sapphires in a great deal of the decorative objects within the collection. Sarpech, swords, and finials from thrones are all dappled with emeralds throughout each century represented in the auction. Though many others are enchanted by the gargantuan Golconda diamond jewelry or the newer works by modern masters such as JAR, the historic emeralds offered by Christie’s in Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence have charmed me more than any others.

See other emerald highlights from the historic auction with the Christie’s descriptions covering the background of the jewels below.

Belle Epoque crescent shaped emerald and diamond brooch formerly in the collection of Anita Delgado being sold at Christie’s in New York. Estimate $200,000 – $400,000 Photo Christie’s

Anita Delgado (1890-1962) was born in Malaga to a modest family of restaurateurs. The strikingly beautiful Anita took to the Madrid stage as a dancer in her late teens. During a performance, she captured the heart of Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala, a charismatic Indian prince visiting Spain to attend the marriage of King Alfonso XIII to Victoria Eugenia of Battenberg. Fiercely protective at first, the Delgado family eventually allowed the prince to meet their daughter. Preserving Anita’s reputation, the Maharaja proposed to the young dancer and carried her off to Paris, where she underwent months of training, emerging as a true Parisienne and Maharani of Kapurthala.

As Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala was among one of the first Indian princes to patronize European jewelers, often supplying them with precious stones from his own treasury to be set in the latest western style, the young Anita also developed a passion for jewelry. A jewel that was of particular importance to the Maharani was a Belle Époque emerald and diamond brooch. This brooch, Lot 132, was designed to highlight an extraordinary crescent-shaped emerald. This magnificent stone originally adorned the Maharaja’s most prized elephant, until Anita admired it and it was given to her on her nineteenth birthday as an award for learning Urdu. Anita often wore this brooch as a forehead ornament at official events and when sitting for formal portraits.

Popularly known as the Spanish Rani, on her marriage Anita took the name Prem Kaur, ‘Love of a prince.’ Over time, the romantic story of her marriage, her candid charm and her great beauty won Anita international fame and she was often photographed and featured in social columns and magazine covers.

Anita Delgado was also a strong philanthropic character, who played a particularly important role in caring for the many Punjabi troops who fought on European fields in World War I. Her marriage to the Maharaja ended after eighteen years in 1925, and with a generous financial settlement she returned to Europe. Her legendary jewels were passed to her only son, Ajit Singh (1908-1982).

An Art Deco Emerald, Diamond and Enamel Brooch by Cartier being sold at Christie’s in New York. Estimate $1,000,000 – $1,500,000 Photo Christie’s

As seen in the archival sketch, this brooch was originally executed with pearls, carved emeralds and diamonds. It was displayed at the the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs and was later reworked by Cartier in 1927 to the current design.

‘The Taj Mahal Emerald’ 141.13-carat Carved Emerald in a diamond brooch by Cartier being sold at Chrstie’s in New York. Estimate $1,500,000 – $2,500,000 Photo Christie’s

The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts took place in Paris in 1925. In a spirit of modernism and innovation, only works of art that were revolutionary in design were accepted. It was an exemplary moment in the Art Deco era.

Cartier presented more than 100 pieces, several especially created for this event, including the famous ‘Collier Bérénice’. Created by the Renault workshop, one of Cartier’s finest, this ornament was meant to be draped over one’s shoulders, hanging at the back, without a clasp. Set with emeralds, onyx, pearls and diamonds, it centered upon an antique hexagonal-shaped carved emerald.

This emerald was later named the ‘Taj Mahal Emerald’ for the carved floral engravings that were reminiscent of the colored stone inlay of the Taj Mahal. Immensely creative, this jewel was widely publicized and appeared in several publications. The unsold pieces from the Exhibition were redesigned by Cartier and the gemstones were used to create new jewels. That was the case of the ‘Collier Bérénice’. The whereabouts of this treasure of nature remained unknown for most of the 20th century, until its re-discovery in the 1990s.

Related Stories:

Who Is Sheikh Hamad Al Thani? And Why Is He Selling His Jewelry

Monica Bellucci Revived An Iconic Jewelry Look

Camp Jewels That Should’ve Been Worn At The MET

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER