Daniel Brush pink diamond and Bakelite picture frame with emeralds and a conch pearl and gold and steel object featuring one of the largest gold granulated domes ever created. Photo Christie's and Departures

Profiles

In Memoriam: Daniel Brush

A craftsman extraordinaire, artist and philosopher

December 1, 2022—“Approach! Commit! Execute!” Daniel Brush told CBS Sunday Morning in 2004 while doing a sort of dance when he was describing his process. The moment captures Daniel, who died on November 26 at age 75, to perfection. Re-watching the segment brought back a flood of memories for me from the late 1990s and early 2000s when I knew Daniel best.

The self-described hermit was beginning to come out of his shell at the encouragement of Ralph Esmerian, the gem dealer and jewelry collector, who had an enormous number of Daniel’s creations. At the time, I worked for Ralph along with Penny Proddow as a curator and archivist. We had access to Daniel’s jewels and enjoyed seeing him somewhat regularly when he visited the office at Rockefeller Center.

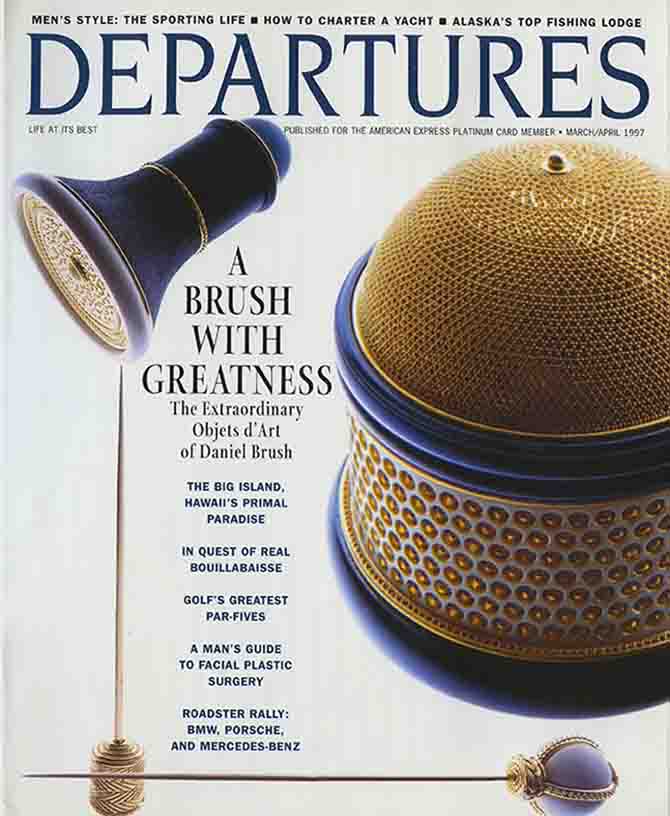

For the March/April 1997 issue of Departures, Penny and I wrote about Daniel in a story titled “A Brush With Greatness,” that I was delighted to find is still on his website. It was published one year before his first major museum exhibit Gold Without Boundaries and the excitement about his work was simmering.

“Daniel gets inside the substance he deals with like Michelangelo gets into stone,” said Paul Gottlieb the former editor in chief of Abrams. “Daniel is spellbinding and hypnotic. He grabs you.” Sotheby’s David Bennett told Penny and I how people were so profoundly moved when he spoke about his work at the auction house in Geneva they were practically in tears.

Daniel was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1947. His father was a merchant and his mother was a writer and photographer who took him on expeditions to museums. When Daniel was 12, they went to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum and he saw his first display of Etruscan goldwork. It was a defining moment in his life. “My heart pounded the way it has not since then,” explained Daniel. “I was insane to learn how it was made.”

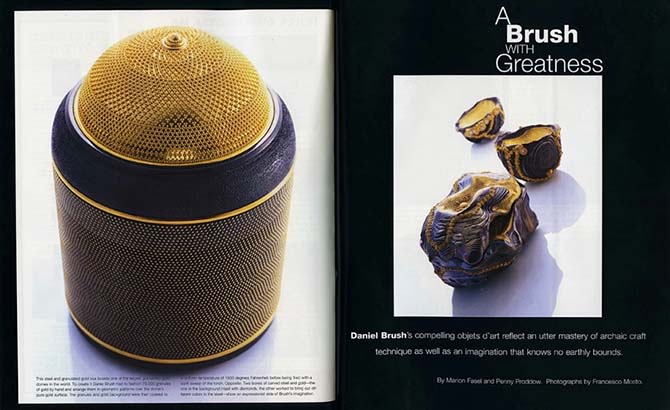

After a foray into academia at Georgetown University, Daniel took up goldwork and learned how to do granulation like none other. The opening image of the story in Departures shows one of the largest granulated gold domes in the world, measuring around five inches in diameter and resting on a cylindrical steel box.

Granulation is a high-wire act of technical bravura. For the dome Daniel arranged 78,000 granules in a geometric pattern over the curved surface. Brush said working up the courage to do the final stage—heating the gold granules and gold background, coaxing both to a uniform temperature and then firing the object with a swift sweep of the torch took almost as long as preparing the piece.

If anything goes wrong—say, the granules fall off—months of work are gone in a flash. Describing the odds of failure, Daniel said, “At 30 seconds it succeeds, at 29 it fails and at 31 it melts.”

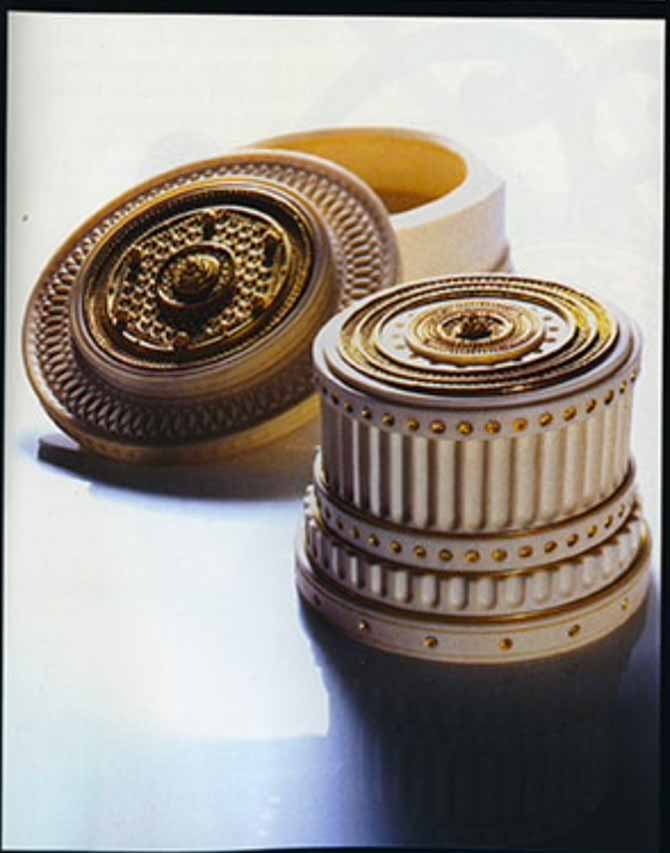

Brush’s restless imagination led him to other arcane areas of craftsmanship during the 1990s. He was a master of the art of turning. A pursuit of royalty during the 18th and 19th centuries, Brush scoured the world to assemble a large collection of antique lathes to conduct the turning in a traditional way. In order to work them he read historic “How To” guides.

To incise patterns on a highly detailed circular box of Mastodon ivory, Brush had to operate three things simultaneously: the foot lever for setting the gears in motion, the headstock for holding the Mastodon and the tool rest that positions the carving blade. A virtuoso display of lathe work, Brush’s boxes have numerous patterns on multiple planes.

In the mid-1990s, at the same time Daniel was working with granulation and turning on his antique lathes, he also made his most whimsical creations. The sweet pieces came about after Ralph Esmerian gave him a parcel of pink diamonds fresh from the Argyle mines in Australia to play around with.

Daniel’s most well-known jewel from this series is the Bunny Bangle. With its pink diamonds sunk in pink Bakelite, the jewel might seem to be an irreverent breakdown of the division between costume and precious jewelry, but hidden in the pretty pink piece are intricate details of craftsmanship. Brush had to hollow out the Bakelite and pierce it with pink gold prongs to hold each diamond in place on the curved surface of the head.

Another treasure from the series is a pink diamond flamingo picture frame. The idea sprung out of conversations Daniel and Ralph had about the Duchess of Windsor’s flamingo brooch and another cache of pink diamonds Ralph had in his vault. The piece is accompanied by a Bakelite and pink diamond screwdriver to be used to open and close the frame.

Since his 1998 exhibition Gold Without Boundaries, Daniel went on to explore many other themes in his work which became world famous. He was the subject of several exhibits including a 2012 retrospective at the Museum of Art and Design. Several books and catalogues have been devoted to his work. Most recently Vivienne Becker penned Daniel Brush: Jewels Sculpture.

Daniel is survived by his wife Olivia who made boxes for his designs and acted as a sounding board to him for over 50-years of marriage. Daniel told Rachel Garrahan in a 2020 New York Times profile that he “describes his wife with the Sanskrit word “Saham” — one of its translations is “I am She” — saying, “My work is her work.”

He is also survived by his son Silla Brush who I believe is a journalist. When Penny and I were writing the story for Departures, Daniel had an impressive Indian motorcycle in his loft. He told us, “I put it together with my son Silla, when he was 10 because I thought it was important that he learn to use his hands.” To paraphrase Shakespeare, we shall not see his like again.

Related Stories:

Daniel Brush: Jewels Sculpture

The Unexpected Story of A Master Jeweler, Pt. 1

Henry VIII’s Favorite Jewelry Designer

Get a gem in your mailbox SIGN UP FOR THE ADVENTURINE NEWSLETTER